This article is part of a long-term project that explores listening as a transformative experience in conflict and post-conflict societies, focusing on the case of Cyprus.1 It explores the ways in which the traumas and legacy of the 1974 Turkish invasion and the continued occupation of the northern part of the island have been acoustically conveyed in everyday life until 23 April 2003, when the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash opened the Ledra checkpoint in Nicosia on the Green Line that divides the island to this day (for Greek Cypriots reactions to the opening, see Ioannou, 2020, pp. 61–62; Demetriou, 2007). Here I focus on the acoustic dynamic of sound as the main means that transgressed the impenetrable limit of the Green Line, allowing for voices that had been silenced to be heard in public, thus disturbing the distribution of who can talk and who can be heard, what French philosopher Jacques Rancière has called ‘the distribution of the sensible’ (Rancière, 2013) and sound-studies theorist Brandon LaBelle has reframed as the ‘distribution of the heard’ (LaBelle, 2010). In doing so, I examine two radio programmes broadcast by Greek Cypriot radio stations, addressed to Cypriots residing on both sides across the Green Line.

My reflections and acoustic experiences are very much approached and filtered through my own positionality: a Greek Cypriot woman born a few years after the war, raised in the southwest of the country, far away from the occupied areas, the Green Line, and checkpoints. Even though my family was not directly affected by the war, this research has made me aware of how growing up in Cyprus implicated all of us in different ways to the traumas and realities of conflict, war, and division. The article draws on textual and archival research (for instance, newspapers and magazines, material from CyBC Archive and Digital Herodotus, and the Cyprus Movements Archive), my own memories growing up in Cyprus and visiting regularly since 1994, and interviews with CyBC journalists, people related to the broadcasts in question, as well as Cypriots who lived on the island in the periods under study. Semi-structured and recorded interviews took place in 2023 and 2024. Interviewees did not wish to be anonymous.

Cyprus Conflict in Brief

Hard as it may be to sum up a conflict that has spanned over six decades, a brief and generalized overview is given here for the sake of context for those not familiar with the case of Cyprus. Conflict in Cyprus visibly began in the 1950s with the rise of militant nationalism in the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. From 1955 to 1959 there was the nationalist armed struggle by the Greek Cypriot National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA) against the British colonial powers, aiming at unification with Greece (enosis). EOKA’s actions created tensions between the Left and the Right within the Greek-Cypriot community (still felt to this day), but also between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. Founded in 1957 by Turkish army officers, the armed nationalist organization Turkish Resistant Organization (TMT) aimed at the island’s partition (taksim) and the unification of part of Cyprus by Turkey: both enosis and taksim as ideological positions were not given up after the establishment of Independence and the formation of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960, but were pursued through parastate organizations, giving rise to bicommunal violence in 1963, 1964, and 1967 (see Ioannou, 2020, pp. 14–32). Violence was triggered by President Makarios’ attempt to change 13 points of the constitution concerning the communities’ representation in government. During the troubles, Greek Cypriots conducted many atrocities against Turkish Cypriots, leading to the latter’s withdrawal to enclaves. In July 1974 a military coup was launched by the dictatorship in Greece, aided by the paramilitary nationalist organization EOKA B that was formed in the island in 1971. Responding to the coup a week later, Turkey used its constitutional right to invade Cyprus in order to protect the Turkish Cypriot population. However, it continued to occupy the island after the coup failed and the dictatorship in Greece fell, also launching a second invasion in August 1974. Since then, Turkey has occupied the northern part of the island.

Some Greek Cypriots and Maronite Cypriots refused to leave their villages in the ‘Turkish-Cypriot-controlled north’ (Demetriou, 2007, p. 992).2They have been referred to as the enclaved people (εγκλωβισμένοι).3 Also, about 200 Turkish Cypriots stayed in the ‘Greek-Cypriot-controlled south’. On 2 August 1975 the Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash and Acting President of the Republic of Cyprus, Glafkos Clerides, signed the Third Vienna Agreement (UN Security Council, 1975). According to the agreement, Turkish Cypriots living in the south of the island could move to the north and vice versa for Greek Cypriots, also specifying that Greek Cypriots who wanted to remain in the north could do so. Even though the Greek-Cypriot side rhetorically turned those who chose to stay in their villages into heroes, instrumentalizing them to a maximum, they were not supported as much as one would expect. In 2017 a reportage by CyBC television featured the enclaved people’s complaints for the temporary interruption of supplies sent to them by the Republic of Cyprus due to taxes imposed by the Turkish-Cypriot authorities. Of interest is the response of an old woman to the journalist’s question about how they were coping: ‘We came to see how the enclaved people are doing, how you’re doing’, she said. Reversing the terms the woman responded: ‘Thank God, my dear, we are just fine. You are the enclaved ones, [those] on the other side’ (Sigmalive, 2017). In the same reportage the woman explained that they lived in peace with the people who came from Turkey, who supported them, refusing to describe them as ‘settlers’, the standard terminology used by the Greek-Cypriot community. I refer to this incident because I want to problematize the notions that I will be using, and also because I would like to show the ways in which voices usually not heard in public can in fact challenge the polarized understanding of certain terms central to a side’s main positioning.

CyBC Broadcasting Post Invasion

After the invasion, the FM radio and television transmitters of the Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation (CyBC) at Kantara Station in northern Cyprus were taken over by Turkish troops and began relaying television programmes from South Turkey, and radio programmes on FM by Turkish Cypriots.4 The Kantara Station covered northern Cyprus and the northern areas of Troodos mountain (CyBC Archive and Digital Herodotus, 1969). Together with the transmitters on the Troodos Station, they covered the entire island in terms of television and radio (ibid.). According to CyBC’s 1974 Annual Report, television transmission was affected by the loss of the Katara station, but also by the destruction of the CyBC headquarters in Nicosia, caused by the bombardment (CyBC, 1974, pp. 14, 16, 17, 98). Television transmission was not discontinued. Ιt was, however, reduced and limited, focusing on covering unfolding events. It also relayed some programmes through the European telecommunications network ‘Eurovision’, but mainly through the Greek National Broadcasting Television (EIRT). The TV relay station at Platres, damaged during the war, was repaired and relayed programmes from EIRT’s station on the island of Rhodes (Greece). Even so, according to the CyBC's 1975 Annual Report, by the end of 1975, a great number of households in the southern part did not have television due to the loss of the Kantara TV station (CyBC, 1975, p. 7).

Utilizing the FM transmitter in Troodos (CyBC, 1974, p.16), the radio operation continued during the war and in its aftermath, playing an important role in providing information about unfolding events through news bulletins in Greek, Turkish, and English, and later – from September 1974 – in Armenian every Sunday. The radio was also crucial in connecting family members and friends who had been separated and displaced during the war and its aftermath. According to the CyBC annual report in 1974, in the first three months after the invasion, thousands of messages of displaced people were transmitted through the radio – a Red-Cross initiative that was realized in collaboration with CyBC. Such was their volume and importance that CyBC was unable to preschedule their transmission, since they were ‘the only live form of communication’ (CyBC, 1974, pp. 14, 33; my translation). According to Foivia Savva, Head of CyBC Archive, and CyBC journalist Angelos Kotsonis (whose voice became synonymous with the live war broadcasts), messages were recorded by journalists on the spot with a mobile sound recorder, as buses arrived with displaced people; I was able to interview both in June and August 2023 at the CyBC Archive. People arriving to the Greek-Cypriot controlled part of Nicosia on coaches of the Red Cross, had to abandon their homes, villages and towns because of the war. Separated from friends and family, whose whereabouts were mostly unknown, they wished to reconnect, but also to let them know that they were alive and well. Hopes of a return never came to fruition, turning them into refugees.

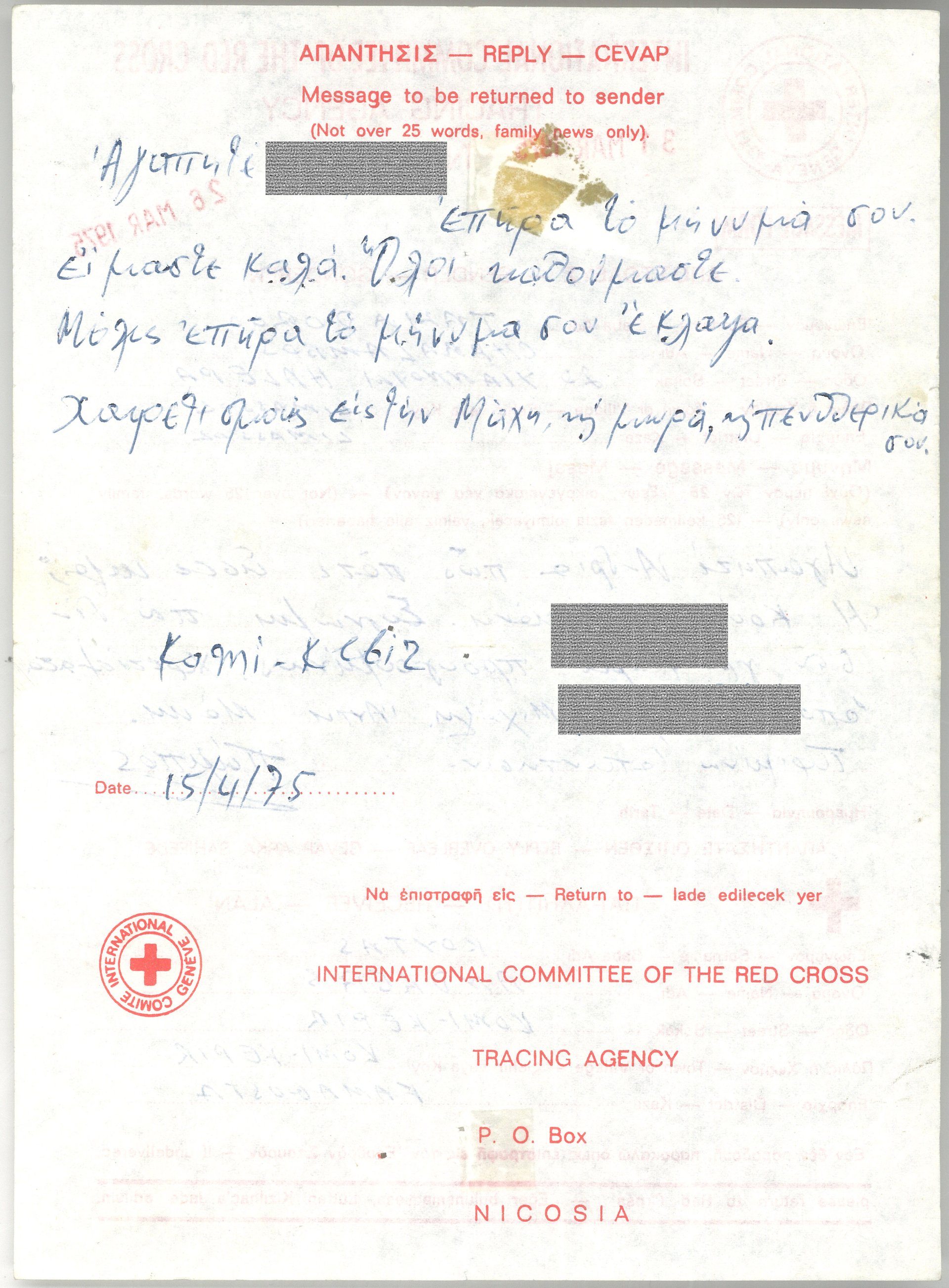

It is not clear to me whether these recorded messages could have been heard in the northern parts at the time, with the Kantara station being under Turkish troops. However, the range of transmission was later restored, and CyBC ran a special programme for the enclaved people for decades, in which messages were read by journalists. In this sense, the radio became the main way and primary space of contact between north and south. There was also the possibility to send brief written messages through the Red Cross. However, these often became a point of pressure by the authorities in the north, regarding whether and when they would be delivered. As freedom of movement was not possible until 2003, representations of the enclaved people were limited to and mediated by official channels, mainly by CyBC radio and later television. In 1997, a UN telephone line – a kind of switch board – was established, which restored a more direct kind of communication (see below).5

‘Messages to the Enclaved’ on CyBC Radio 1

The main radio programme that supported an indirect kind of communication between the enclaved people and their families and friends was ‘Messages to the Enclaved’, broadcast every day on CyBC Radio 1 after the lunchtime news. The programme was the evolution of the above-mentioned Red Cross initiative of recording messages in 1974. According to Phoevia Savva, in later years CyBC journalists would also visit refugee camps or would invite refugees in places like schools during the Christmas or Easter holidays to record messages to their enclaved friends and family; these were then transmitted as a special programme (see, for instance, CyBC, 1989).

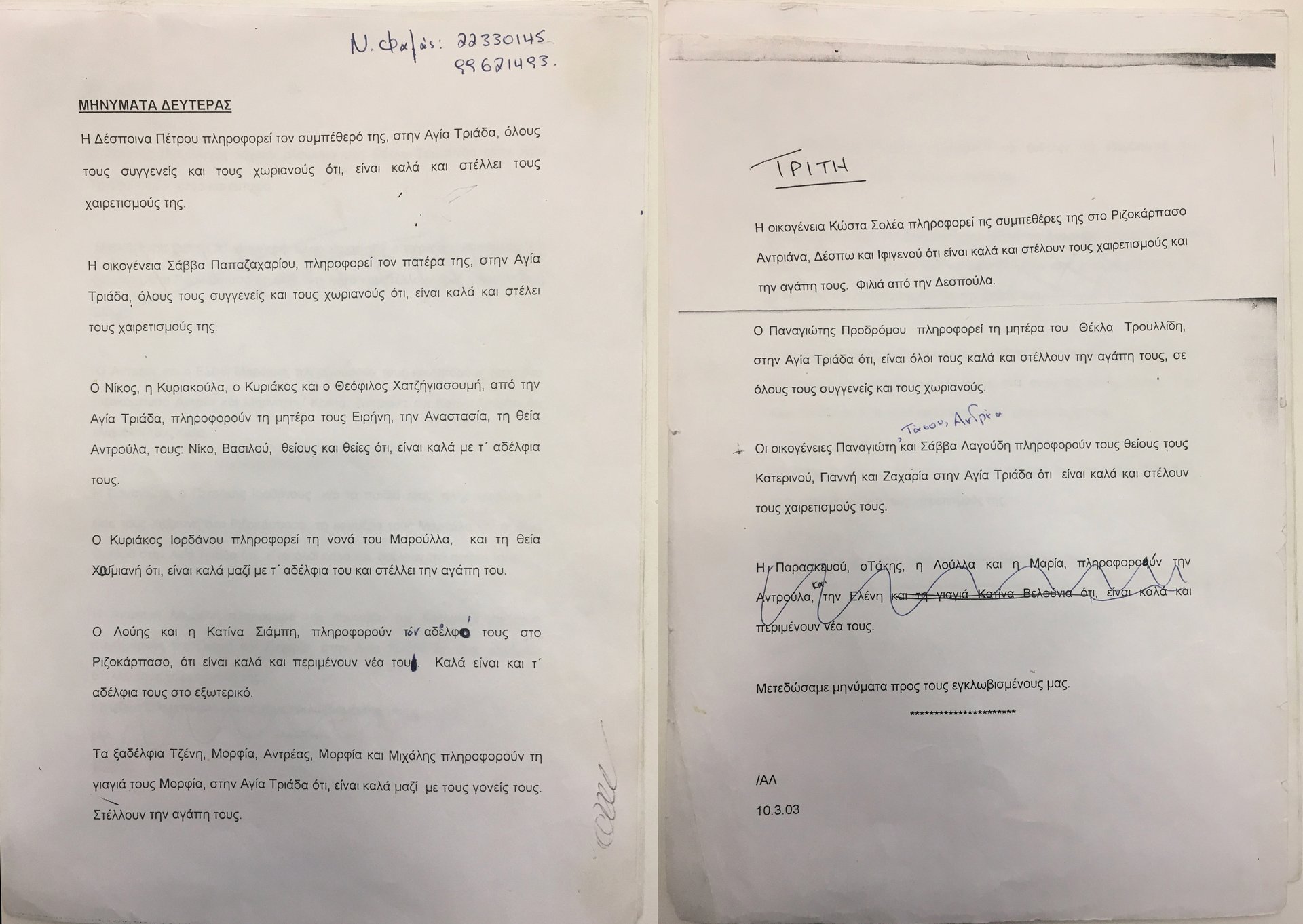

I focus here on CyBC’s ‘Messages to the Enclaved’, which ran for decades. A service was set in place at CyBC in which friends and family in Cyprus and abroad could call and dictate their messages. These were read daily by a journalist, usually a woman, right after the news bulletin at 13:30. This was a time of high listenership since in the 1980s and early 90s information primarily came from state radio and television. Νo recordings of the messages exist. Nor is there a detailed archive. The only traces I was able to find were a few printed messages, some from February but mostly from March 2003: that is, a month before the first checkpoint was opened on 23 April 2003 (see Ioannou 2020, pp. 55–71; Demetriou 2007, pp. 993–999; BBC 2003). Though I have not been able to trace the moment when the programme was discontinued, it seems that it was phased out after the opening of checkpoints, when people began visiting north and south en masse. The messages I found were given to the CyBC archive on 7 January 2019, as noted on the front page of the batch. Despite any minor differentiations, all of them began in an identical manner:

Kyriakos Iordanis informs his godmother Maroulla and aunt Chomiani that he is well with his siblings, and he sends his love.

[BREAK]

Louis and Katina Siampi inform their brother in Rizokarpaso that they are well and are waiting to hear from him. [BREAK] Also well are their siblings abroad.

[BREAK]

Panagiotis Prodromou informs his mother Thekla Troullidi at Agia Triada that they are all well and are sending their love to all relatives and fellow villagers.

[BREAK]

The family of Kosta Solea informs their mothers-in-law at Rizokarpaso Antriana, Despo, and Ifigenou that they are well and send their regards and their love. [BREAK] Kisses from Despinoula.