I’m concerned to reflect upon listening in relation to the missing and the disappeared, to think listening as what allows for navigating the complex, difficult reality of absence. These are absences marked by trauma, by original wounds of broken cultures and languages, and that are often carried as part of inner life. And moreover, that figure themselves in the stories and expressions of a people. How are such original wounds carried in ways that navigate their difficult presence? What methods emerge that help one keep going, lending to ways of resisting and healing? As part of this, I’m concerned with the ways in which memory itself, and the perception of an inner life, is often made accessible through an intuitive understanding of listening as a capacity. By way of turning inward, listening affords a type of poetic sensing of the unseen world of inner life. Is not listening often called upon as a means for approaching past experiences, especially those marked by trauma and loss, and which are often held in silence? Listening to oneself is often what allows for attending to the emotional, psychological labour of healing, contributing to processes of recall and witnessing, and the possibility of telling a different story.

Alongside the inner work listening supports, understandings of inner life often carry an auditory or acoustic vocabulary; from the unbreakable silences to the echoes of past experience, from the noise of inner thoughts to the resonant sympathies by which affective connections are felt, inner life is a reverberant arena – what Steven Connor terms ‘the inner auditorium’ of the self (Connor, 2009). To attune to the complex noise as well as prickly silence of memory is to cast inner life as an acoustic dimension, where the reverberations of past experience resound – and which listening finds ways of acknowledging.

By way of listening, inner life is brought forward, animated, placing listening as central to processes of self-realization and repair. Listening is a calling forth, drawing toward itself all that is often hidden, suppressed or unclear, and in need of understanding. As Jean-Luc Nancy suggests, ‘to listen is to be straining toward a possible meaning and consequently, one that is not immediately accessible’ (Nancy, 2007, p. 6). While listening aids in the search for guidance, found within the chambers of an inner world, it is through being another for oneself – to speak to oneself, to carry the voices of others, to hear all the humming within – that inner life is made approachable. Listening, as Nancy proposes, evokes the self to itself, making of it an ‘omnidimension’ – to be at the same time outside and inside (Nancy, 2007, pp. 13–14). Following such perspectives, listening emerges as a method, one that assists in navigating difficult memories, and how it is one may come to live with absence. Yet, listening is never a smooth undertaking, nor is it always readily available and immediately beneficial. Listening may also be the very source of pain, injury, trauma – the hearing sense is markedly susceptible to the force of an external world, and is instrumentalized in any number of systems of violence. At times, one may not want to confront all that listening elicits. Additionally, when it comes to extreme forms of oppression, the possibility of hearing oneself is brutally blocked, if not annihilated. This finds critical examination in Kelly Oliver’s important work on witnessing. As she argues, the capacity to bear witness to experiences of violent oppression, including the work of testimony, is crucial for repairing subjectivity (Oliver, 2001).

To consider listening’s role in navigating absence, and related psychological and emotional injuries, I want to follow two threads; these include, first, addressing listening as remembering, as inner work, one that assists in carrying that which refuses to go away, and second, listening as witnessing, specifically opening onto what cannot be witnessed, that of the erased.

Listening as Inner Work – Being One’s Own Witness

In the article ‘Archive of Silence: on Intergenerational Memories of Gendered Trauma’, the researcher Jana Kriechbaum maps a generative relation to the affective archives constituted by past experience. These are archives held in the body, and whose meanings are never readily available; rather, affective archives require a continual work as well as the finding of self-created methods. The question of affective archives emerges for Kriechbaum as a personal question, for as a researcher she wonders as to the influences such archives have on knowledge practices. As she suggests, research itself is prone to a form of entanglement with the researcher’s own life and memories, the psychological and emotional strata held in the body and that informs what it means to re-search. While research, and subsequent academic output, often presents itself as separate from the researcher’s own embodied experiences full of the desires, the physical realities, the unspoken leanings and emotions of personal history, Kriechbaum works at finding ways of giving room to private life – threading together the intimate sphere of feeling and the work of research. That is, to consider affective archives as contributors rather than burdens. Such concerns partly become the content of her work and gives way to an engagement with what she highlights as ‘archives of silence’ (Kriechbaum, 2022). In particular, in her autoethnographic work on intergenerational memories of gendered trauma, Kriechbaum writes a letter to her grandmother, opening an imaginary space for contending with the silences of shared trauma passing between grandmother and granddaughter. Through such a textual space, silence emerges less as an obstacle or burden; rather, Kriechbaum begins to recognize in silence a form of kinship. As the author writes to her grandmother, ‘I wonder if there is an intergenerational understanding that you and I share when speaking in silence’ (Kriechbaum, 2022).

Kriechbaum’s work comes to complicate the dichotomy of silence and speech, allowing for a performative shift in what counts as agency and articulation. While agency is mostly understood by way of vocalization, a sounding forth by which to make a claim onto the spheres of representation and participation, Kriechbaum draws attention to silence as a potential method. Archives of silence may, in fact, be deployed through enactments of quiet refusal, imaginary communion, creative research, and writing that narrates otherwise what it means to carry pain; silence, by way of such gestures, is put to work in negotiating trauma, drawing from it a range of complex echoes that assist in figuring emergent forms of partnership. In short, the silences held within are made to resound in unexpected ways; rather than to hear silence as absence, Kriechbaum finds within it a medium or communicative channel.

Such perspectives are suggestive for appreciating how inner life is often made accessible by way of listening’s reach; listening is located as a (literal and metaphoric) capacity that affords ways of holding past experiences – listening may be called upon to engage the silence within in order to discover truth or realization, yet it may also afford other methods, other imaginaries. To listen may also be about ‘holding a relation to suffering’ in ways that become transformative. This finds further expression in Nirmal Puwar’s insightful article ‘Carrying as Method: Listening to Bodies as Archives’. Puwar considers the ways in which people come to carry a range of past experiences. The notion of carrying which Puwar draws out speaks to the sense in which individuals are constituted by a complex array of things, from memories and images, desires and voices to intergenerational stories and family histories, genetic lineages and feelings for the future: a constellation of complex and persistent matter whose effects discordantly rest within the body. As Puwar suggestively posits, ‘carrying has a physical resonance’ that makes of the body a vessel, an inner dimension whose complexity requires ways of listening (Puwar, 2021).

The notion of carrying as method which Puwar maps is suggestive for capturing inner life as a reverberant, acoustic dimension, where feelings and affects echo across the inner territories. These are the physical resonances Puwar identifies as central to carrying – resonances that unfold the body as an omnidimension which, as Nancy suggests, shows the self as outside and inside at one and the same time. How to endure the effects of such inner echoes? In what ways can the ceaseless noises of inner life be heard and made meaningful? Carrying is performed through a range of acts and gestures, some which take the complex lineage of intergenerational silences of endured violence (as in Kriechbaum’s case) as the basis for new forms of kinship, and others which attend to unspoken memories through the citing of others and whose voices lend support to the stories we may tell. The archive of silence is an echoic jumble of experiences and voices, recollections and embedded memories, and from which listening emerges as an essential form of carrying: in evoking the self to itself, listening may draw forth that which is held within.

Through Puwar’s and Kreichbaum’s critical and creative works we are given a view onto inner life as resonant, as silent, as dissonant; archives of affect are attended to through ways of listening which, as the craniosacral therapist Susan Raffo argues, is fundamental for personal and collective repair. In Liberated to the Bone, Raffo offers a range of insightful perspectives onto questions of health and healing, as well as listening’s contribution to care work. As a therapist, Raffo focuses on finding ways of attending to the body and all that it comes to carry and endure. Fundamentally, this entails recognizing not only the immediate injuries some may suffer; Raffo brings attention instead to the ways in which bodies are burdened by histories of violence that may span generations. As she highlights, ‘There is impact with violence, there is impact with pleasure, and then there is what happens after that impact, the echoes that carry forward’ (Raffo, 2022, p. 59). For Raffo, and for the broader cultures of care work, what we know of the body is never strictly confined to the experiences of individuals and immediate symptoms or pains. Bodily life, instead, is recognized as part of a greater whole that includes a range of social, psychological, emotional and spiritual dimensions and experiences. Furthermore, bodies are histories in themselves, biological, genetic, cultural, social, political histories that define much of their abilities and tendencies. Our bodies are the manifestation and expression of all these histories, the intergenerational lineages and social, cultural genealogies, the languages and meanings that inscribe a plethora of defining values and viewpoints, that emplace and orient in certain ways, and that often lead bodies into particular forms of strain. As Raffo argues, to work at healing is never strictly about individual health; rather, healing is a political act, one that directs itself toward the larger project of healing justice.

Importantly, Raffo brings focus to the deep or slow violences inherent to settler-colonialism and systems of racialization that have negatively affected generations of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour in particular (in the context of North America, which is the main focus of the author). These unfinished histories wield their influence onto the physical wellbeing of individuals and communities, but they also carry over onto the land itself. ‘What does it mean to do healing work, to do any kind of change work when the land below your feet still carries stories that are not finished?’ (Raffo, 2022, p. 12) begins Raffo’s Liberated to the Bone. These are ‘original wounds’ perpetrated by settler-colonialism, and the imposition of systems based on the owning of land and people (Raffo, 2022, pp. 16–17).

In calling attention to the original wounds of land and people, Raffo seeks to ground her practice, and the work of healing in general, recognizing that if one is going to attend to individuals that seek care, it is essential to know of the unfinished histories that ‘shape the space of our practice and the people who come to see us’ (Raffo, 2022, p. 22). Importantly, pursuing the work of healing justice necessitates that such knowing is undertaken not only ‘with your mind’ but with ‘your whole self’: ‘When I use the phrase “healing justice”, I am reflecting on how the systems we seek to change outside of our bodies are also carried within our bodies’ (Raffo, 2022, p. 25). Knowing of unfinished histories, the genealogies of violence, carried as original wounds into the life of a society, is to know by way of the whole self, knowing of one’s own participation or place within particular systems. Such knowing, as Raffo argues, is possible only by way of ‘the felt sense’, which comes to communicate by way of poetry: ‘The cells of the body communicate with us through poetry, through story, image, and metaphor. This is how we end up with a felt sense of something rather than only an intellectual understanding.’ Extending Kriechbaum’s and Puwar’s creative reclamation of the body as a path toward healing, Raffo suggests that ‘this felt sense, this way of knowing from the body up, is how transformation takes place’ (Raffo, 2022, p. 25).

From carrying as method and speaking through silence to the care work that aims at repairing original wounds, processes of healing are facilitated by way of listening’s inward reach. A care of the self is never only expressed through the inner voice of logos as Michel Foucault argues; rather, inner voicing is equally an inner listening: the sounding of routes by which to ‘unfreeze the body’ as Raffo suggests, allowing for movement again. Listening to oneself gives greatly to becoming witness to oneself: witness to the complex matter of inner life, the sedimented layers and embedded wounds, those things one comes to carry and which listening allows for ways of knowing that extend over or below verbalization. As a care of the self, listening gives room for holding, by way of a felt sense, the silences, the noises, the echoes that constitute an inner world.

Listening and the Negative – Disappearance Refigured

Moving from acts of carrying, as a listening that supports ways of holding trauma, I want to shift to consider listening in relation to a greater social, political context, and where original wounds are inflicted. This includes a consideration of the disappeared in the context of the military dictatorship of Pinochet in Chile (1973–90). While listening wields a profound effect onto struggles for social recognition, affording more considered dialogue and situations of being heard vital to political agency, such processes are deeply strained when confronting the difficult reality of disappearance. In fact, disappearance is enacted in order to break social communities and block political process as shaped by democratic constructs of social equality and justice. How to act as witness to that which is missing? In what ways is it possible to address the unseen figure of the erased, in ways that give recognition to the disappeared? Are there ways of listening that might attend to the original wounds of a greater social body in order to restore social communities?

Following these questions and concerns, I want to consider the ways in which disappearance came to shape people’s realities during and after the dictatorship (under the Pinochet dictatorship, more than 3,000 people were disappeared, and approximately 30,000 people were incarcerated and tortured, not to mention under constant surveillance as well as exiled). For many, the violence of the dictatorship was enacted not only through direct assault, which in itself was brutal, but equally by creating an oppressive atmosphere of imminent death – the death that awaits and whose terror is expressed precisely as a present absence: the erasure that is ever-present but unspoken, unnamed, and whose enactment is performed behind closed doors. The quality of a present absent gestures toward the ways in which Michael Taussig defines the captivating grip of the public secret (Taussig, 1999). As Taussig suggests, the public secret forms a mask to dominant power; it is a carrier of power, showing itself as a hollow form, where true meanings are openly acknowledged but never spoken of. In short, the public secret is a mechanism by which we come to know what not to know.

The reality of disappearance under the Pinochet dictatorship, with its hidden rooms of torture and the insidious policing of society by military death squads, subsequently generated an artistic, literary culture grounded in a relation to the negative. Within such a culture, negativity formed the basis for negotiating the debilitating force of a public secret. For example, Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA) were at the centre of a larger cultural community whose performative actions sought to confront the reality of violence through obscure languages, or a general poetics (as well as psychoanalytics) of meaning that often moved art onto the streets – thereby wielding an ambiguous presence, as these were actions that were hard to identity as art as such. This finds expression, for example, in Lotty Rosenfeld’s now iconic action Una milla de cruces sobre el pavimento (A mile of crosses on the pavement). First enacted in 1979 on Avenida Manquehue leading into Santiago, the work is comprised of Rosenfeld adding perpendicular white lines to the existing ones demarcating separate lanes, thereby covering the avenue with a series of white crosses. Making reference to the unmarked grave, Rosenfeld works at crafting a symbolic language by which to identify the unidentified.

The artist and writer Diamela Eltit also developed important work in this context. As a member of CADA, Eltit equally engaged with the complex conditions of the dictatorship shaped by the realities of disappearance and whose work took guidance through references to sadomasochism. For example, in the performance Maipu from the Zone of Pain series (1980), which took place inside a brothel in Santiago, Eltit cut and burned her arms and legs while reading aloud sections from her first novel Lumpérica which describes a female character enacting the very actions the author performs. After the reading, Eltit proceeded to wash the pavement in front of the brothel, scrubbing it clean while on her knees. The act of self-inflicted pain had a powerful resonance in a country marked by the horrors of violence and torture; and Eltit’s conflation of self-abuse with the cleansing of the street outside gestures toward images of self-sacrifice, in which the artist seeks to ceremonially placate the hidden powers of the state. These are gestures that attempt to carry the original wounds, symbolically gathering the pain of the country in ways that navigate its brutal meanings.

Acts of self-mutilation find further expression in Raúl Zurita’s poetic work Purgatory from 1979, a book whose cover shows Zurita’s face with self-inflicted burns; this was extended in 1980 when the poet tried to blind himself by pouring ammonia into his eyes – all of which reference his own experiences of torture. Taking the body as a site or surface of negotiation with dominant power, self-mutilation emerges as a gesture by which to reclaim the body as one’s own, to rehearse one’s own death. Such an approach is embodied in the works of Carlos Leppe, a performance and video artist whose work The day that you love me (1981), for example, shows the artist in states of collapse as he speaks to a video recording of his mother (who had been tortured by the military); or in Elías Adasme’s iconic photographic piece depicting the artist hanging half-naked upside down from a sign of a metro stop in the city of Santiago, a performance that anticipates an experience of torture yet to come.

All of these works gesture toward the negative, disappearance, and the general state of violence defining daily life under the dictatorship. Furthermore, they start to suggest a performative process by which to witness precisely what cannot be witnessed: that which is disavowed, withdrawn, erased. As enactments, they can be appreciated as methods for contending with the unspoken and untellable secrets that were to pervade Chilean society at the time, giving forms of embodiment to the silenced realities of disappearance. They can be seen as manifestations or byproducts of a state of witnessing an unbearable reality; witnessing the painful absence left behind through the removal of friends and family, artists positioned their own bodies as records, documents whose surfaces collect the violence of disappearance. Returning to Kriechbaum’s reflections on the body as an affective archive of silence, the artistic works emerging in Chile during the dictatorship approach the body itself as an archive of a present absence: as the carrier of a history that will have no record.

These views are given a more contemporary expression in the works of Voluspa Jarpa, a Chilean artist living in Santiago. In particular, Jarpa has focused on working with the dossier of CIA documents accumulated during the dictatorship and declassified in 1999 and 2000 under President Bill Clinton. Importantly, upon their declassification the documents were expected to contain valuable information that could shed light on missing persons and the operations of the military. Yet, upon release the documents were heavily redacted, thereby enacting another form of violence, one that compounds the reality of disappearance and erasure: to inflict a sort of ‘double trauma’.

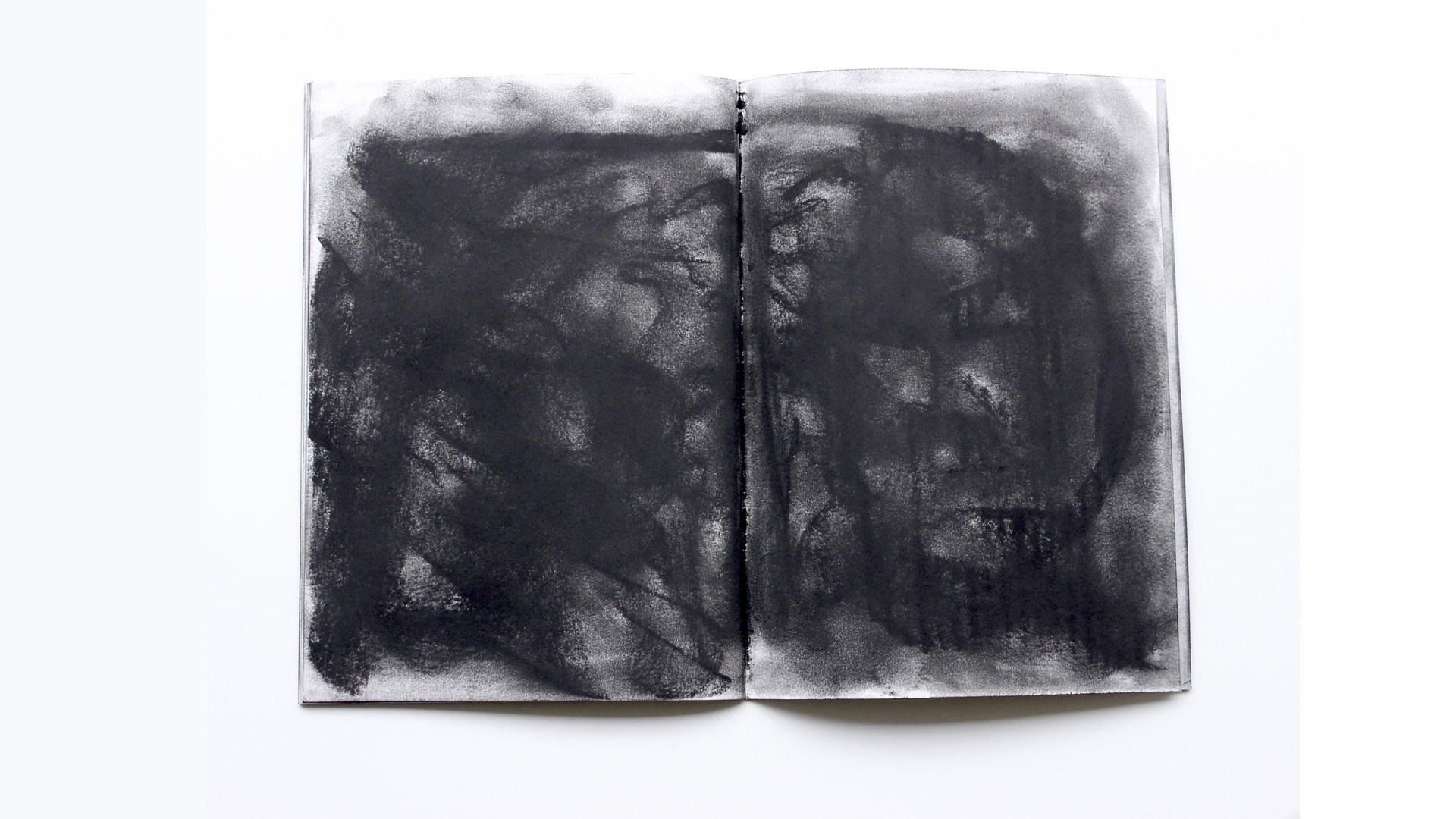

One particular work by Jarpa, Biblioteca de la No-Historia / Non-History (2010) is comprised of a set of books meticulously compiling the CIA documents, and which are subsequently inserted into bookstores and libraries. The artist poses the question to audiences: ‘what space will you assign to this book?’ and later, ‘what will you do with this book?’ Such a library becomes a carrier of an impossible reading, asking of us to confront the missing – to attend to the absence at the centre of history: to shift an approach to reading, where meaning is to be found in the black. The archive of silence Jarpa works at materializing is marked by paradox and unease; it is a silence that calls for a shift in knowledge production – it is a knowledge grasped by way of the negative.

*

The particular works I’ve been outlining help expand upon the ways in which listening assists in approaching the disappeared, the missing, for attending to the silences often underpinning what is seen and heard and known; they further assist in moving from the inner world to that of the outer, and the complex movements of a social, political life – especially those marked by absence, emptiness, and political violence. These are works that articulate methodologies emerging by way of the negative. Here, I’m tempted to suggest that Jarpa turns the black of the redacted documents into a silence that resounds; her works come to position us less as readers and more as listeners, requesting of us to dwell with the erased: to hold a connection to suffering. I might hear her library as a type of negative work whose compositional ordering sounds a (no)historical record; it makes of the redacted a memorial by which to commune with the dead, to open an impossible conversation with erased history.

The anthropologist Yael Navaro develops the concept of ‘negative methodology’ as a way to contend with the realities of disappearance and loss as well as histories marked by the missing (Navaro, 2020). In particular, she seeks to address the remains of political violence, the fragments and the ruins – what happens when we are left with ruins? As she notes, acts of (anthropological) research and the project of finding truth often proceed by trying to put the pieces back together; to fill in the gaps, the silences of broken communities, in an attempt to solve the problem (often through gestures of reconstruction) of unfinished history. In contrast to this rather ‘positivist’ method, she calls for a ‘negative methodology’. Negative methodology is a counter-methodology, one that does not aim to give voice to the voiceless, but rather holds the tension between history and truth, between the remains and the need to know; negative methodology wields a refusal to complete the narrative, to capture history within a totalizing representation, instead, it keeps within the gaps, asking us to attend by way of the emptiness, the shards, the absent – a research approach that ‘stays in the fissures, rifts, enigmas, and hollows of knowledge production’ (Navaro, 2020, p. 162). These are gestures and positions that draw out ‘the ethnographic research imaginary’, suggesting parallel routes to that of ‘evidentiary knowledge making’ (Navaro, 2020, p. 162).

Negative methodology is marked by what Navaro terms a ‘methodological pessimism’ (Navaro, 2020, p. 164). Such a pessimism is positioned as generative of sensing, researching and attending to the aftermath of political violence in ways that specifically allow for not-knowing, or that prompt a research positionality marked by frustration, lack, when sites may resist the researcher’s desire to find out, to finally hold and thereby make present that which is terribly absent. The methodological pessimism posed by Navaro is therefore one that may effectively interrupt assumptions and expectations, turning one toward the jagged reality in which truth may never be found. Such a position may lead anthropology, and the ethnographic imaginary, toward a consideration of not so much what is visible, evident, present, but what is absent – and importantly, what has been made absent or emptied out – and which calls for other forms of study.

This is not to suggest that evidentiary work, the capturing of facts and the telling of what happened are less valuable – these are intensely needed. One may think of innumerable scenes of political violence in which living with ruins is unbearable, and where gaining truth or speaking outright is radically transformative; yet, negative methodology offers an important perspective, suggesting counter-intuitive routes and techniques.

One particular example Navaro cites is that of Saidiya Hartman, whose work on slave histories comes to challenge how it is one may grasp missing individuals, communities, cultures. Hartman addresses the cultural and epistemic violences perpetrated by the Atlantic slave trade – violences whose records are marked by absence, voids, by erased identities – a violence which ‘resides precisely in all the stories that we cannot know and that will never be recovered’ (Saidiya Hartman, quoted in Navaro, 2020, p. 164). Rather than write a ‘coherent narrative’, Hartman proceeds by way of the ‘incommensurability’ between a commitment to history and what the archive does not provide, between the irretrievability of slave history and the drive toward narrative. Consequently, her work proceeds by way of a ‘narrative restraint’ whose performance lends to a reconceptualization of knowledge production.

Concerns for how to give narrative to that which resists knowing finds further articulation in the poetic work Zong! by M. NourbeSe Philip, a work that equally attempts to address the violence of slavery. Zong! is a series of poems referencing an incident that occurred in the 18th century aboard an English slave ship; having set sail from the west coast of Africa for Jamaica, the ship Zong was severely delayed due to navigational errors. The delay led some of the ‘cargo of African slaves’ to die of illness and lack of water; it further provoked the captain and crew to ‘throw 150 slaves overboard’ in order to ‘preserve’ the rest of the cargo, subsequently enabling the ship’s owners to collect insurance on ‘lost property’ (Philip, 2008). The incident led to a court case in which the insurers were obliged to pay the ship’s owners for the loss. Philip’s approach to addressing the violence of slavery, and the particular brutality of the Zong case, is to write by way of the legal documents, court case summary and the insurance claim. These function as the basis for Philip’s poems due to the fact that, as the author highlights, ‘The only reason why we have a record is because of insurance – a record of property’ (Philip, 2008, p. 191). The insurance document and legal texts are understood to both contain and mask the story of the Zong incident, and in doing so, they come to exacerbate the violent withdrawal of knowledge as to the identities of slaves: the slave has no name, rather, the documents state an ‘inventory of property’, which leads Philip to suggest that silence is its own language. It is a language that must be written somehow, and which directs the author toward a particular strategy, one that moves from the loss of the name, legally held under as ‘lost property’, toward an occupation of that absence – ‘to lock myself into this particular and peculiar discursive landscape in the belief that the story’ of these murdered people ‘is locked in this text’ (Philip, 2008, p. 191).

Zong! is a writing that performs its own restriction, its own confinement; it pins itself down within the legal record, to pick apart the left behind documents, selecting verbs and nouns from its lines in an act that parallels the way slaves were selected. These are gestures enacted onto the documents, a cutting, a pulling apart, resulting in ‘semantic mayhem’ from out of which signs of new life may appear, and one may read the ‘untold story that tells itself by not telling’ (Philip, 2008, p. 194). They emerge as negative strategies that unsteadily mark the page with broken words and deep silences, jagged sentences and drowned meanings, and that stagger the author in her attempts: ‘The poems resist my attempt at meaning or coherence and, at times, I too approach the irrationality and confusion, if not the madness, of a system that could enable, encourage even, a man to drown 150 people as a way to maximize profit’ (Philip, 2008, p. 195). Philip’s unsettled and unsettling work arranges for an altogether different form of writing, one akin to Hartman’s narrative restraint: to formulate a means, a path, a madness so as to tell without telling.

Hartman’s and Philip’s approaches to engaging with histories of slavery draw forward forms of writing or textualization that may help elaborate how it is original wounds are carried. As Krista Ratcliffe and Kyle Jensen highlight, rhetorical situations – as situations marked by the urgencies of communication, of speaking, listening, writing and narrating – are often underpinned by ‘unstated hauntings’ (Ratcliffe and Jensen, 2022, p. 79). These are hauntings that carry an unfinished relation to history, where memories of people and places (and their erasures) call out for ways of telling, restoring, and that come to impact onto how one may communicate about often difficult issues. ‘Rhetorical listening’ is positioned by the authors as a path for better acknowledging the sedimented layers of rhetorical situations, and the ways in which one may write more carefully, holding a relation to the unstated hauntings nested within given places, histories, communities. As Hartman and Philip both reveal, writing so as to memorialize what or who has gone missing demands a deep tussle with existing as well as missing languages, archives, records and histories. From narrative restraint to semantic mayhem, writing as listeners opens paths toward hearing the voices of the unidentifiable and the removed.

In following these negative strategies and methodologies, from the self-inflicted injuries and blacked-out readings found in the context of Chilean art to the re-textualization of existing historical documents marked by violent withdrawal, I’m led to pose the concept of negative listening as a listening that may assist in approaching the disappeared and the erased on their own terms; that delays listening as what tries to hear and, in doing so, may too easily fill in the gaps. Instead, a negative listening is positioned as what keeps one close to a more nuanced form of listening, an uncertain, pessimistic listening, especially in terms of recognizing how the inaudible may resound in the negative.1 A negative listening is listening in broken times, it is to listen by way of the ruins, the remains, and what they (with)hold; a listening adept at holding a connection to absence, attuning to traces left behind, and which can figure itself in the fissures, the silences, the voids. Negative listening moves amongst the fragments to pick up stray frequencies, those which hover under or above hearing range, the vibrational murmur or deep humming that carries the dead. These are ways of listening that listen-against official narratives, to gather from the pieces a range of echoes carried over from those killed or gone missing. Negative listening is shadowy work, supporting modes of dark navigation, especially when confronting erasures and a lack of documents, a blind trajectory into the madness Philip speaks of, and through which one may come to witness that which cannot be witnessed.

Negative listening, as I’m concerned to emphasize, is a form of listening that does not necessarily search for answers, to finally hear the voiceless or the missing; rather, it calls for staying in the gaps – to inhabit the difficult reality of the inaudible and the unheard. A listening that may travel into the waters, the unmarked graves, the emptied grounds of violence, in ways that re-politicize that which may come to pass as official history. These are listenings that attend to jagged stories, stolen breaths, denied voices; listenings that are urgently needed, and that contribute not only to the ongoing writing of history, but also to the understanding of listening’s role in struggles for justice – to extend the limits of listenability toward that which is missing or ruined.

Negative listening is conceptualized as what may contribute to the methodological figures of rhetorical listening, of methodologies that seek to perform by way of the erased; a negative listening that follows the traces, that acknowledges the gaps present within any public world or community, that also refuses to gloss over the cracks, the rough edges, the remains that silently call out. Here, listening may interrupt itself in its desire for fulfillment, for capture – to recognize the limits of listening as what tries to witness. Listening, by way of a methodological pessimism, can stagger itself, forcing one to stay with the gaps, the broken lives, the original wounds, those instances when communities may never be restored. These are difficult listenings, and yet, they are crucial, leading one to attend to the debris; to find strategies for going on, ever-more carefully, turning one’s listening toward those who dwell in the shards.

Poetics as Wit(h)nessing – from Refusal to Repair

Considering the enigmatic movements of a present absence, and how archives of silence are carried in the body and on the streets, I’m interested to think in what way certain forms of listening as witnessing are guided by a poetic sensibility or knowledge. As I’m concerned to pose, poetics lends to figuring routes in and around the complexities of disappearance; it contributes to finding ways of listening into the dark, opening a means for attending to the erased. If listening emerges as a gesture by which to approach inner life, as a dimension full of the reverberant echoes or silences of memory, aiding in communing with the missing, the silenced and the transgenerational – to listen across dimensions of the seen and unseen, heard and unheard – is it not suggestive for a poetic way of knowing?

Following Fred Moten’s proposition that poetics is a refusal of enclosure, I’m interested to think listening as a poetic capacity. To listen inwardly, so as to carry all that is held in silence, or in turning outward, in ways that help navigate the erasures left behind by systems of political violence, comes to express a poetic position: to refuse to accept the enclosures of meaning, history or truth performed by dominant powers and the very systems that normalize violence. Rather, poetics (as knowing, as practice, as sensibility) interrupts the demarcations set in place between the rational and irrational, sense and nonsense, the living and the dead. It keeps to the outside, performing as fugitive – as that which escapes the enclosures of language, meaning, and in doing so, opens onto a social energy, a dynamic of aliveness. Such poetic understandings or positions are aligned with the vitality of sensual life, the flourishing of imagination and the search for connection; it works against ideologies of death and the corralling of land and persons. In this way, poetics functions as what the Indigenous scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer terms a ‘grammar of animacy’ in terms of the ability to ‘see life in the object’ (Kimmerer, 2020, p. 49). And which understands language as a being in itself. As Kimmerer argues, ‘Science can be a language of distance which reduces a being to its working parts; it is a language of objects. The language scientists speak, however precise, is based on a profound error in grammar, an omission, a grave loss, in translation from the native languages’ inherent to the natural world’ (Kimmerer, 2020, p. 49). In contrast, a grammar of animacy is shaped by recognition of the ‘unseen energies that animate everything’ and where words become gestures of evocation, ceremony, reciprocity, a breathing.

It is such poetic fugitivity and animacy that I find in listening as well, and which to my ear contributes greatly to the work of witnessing. Listening provokes a relationality that extends the arena of the immediate and the known – while listening is clearly central to an ethics of difference, in terms of holding a space for hearing the other, it is equally the capacity to relate to that which extends relationality itself. That is, as a grammar of animacy listening is precisely what opens us to ‘the energies passing through all things’ (Kimmerer, 2020, p. 55). From listening as a capacity for a care of the self, a method of carrying the archives of silence that populate inner life, to the capacity to hear the blacked-out and the erased, the invisibilized – attending to the lives of drowned African slaves or the disappeared thrown into the sea off the coast of Chile – listening makes possible an ethics of recognition that extends precisely toward what I may term the other-other. Listening supports all types of relationships, contributing to the conversations we may have, and the political acts of recognition fundamental to democratic society, but it does so by also exceeding what we may know of relation: listening, rather, exposes us to the peripheries of knowability, recognizability, the apparent, and legible. This finds echo in what Bracha Ettinger terms ‘relations without relating’ (Ettinger, 2006), fundamental to an elaborated understanding of ethics, of what it means to be responsive to a shared world, especially in relation to those we may never see and that may, in fact, not even be human. Within this scene of poetic fugitivity, of negative listening, relation is not only the knowing of the other, but an encounter with what exceeds knowability and that we tend to by way of the felt-sense and the poetry of the body which, as Susan Raffo highlights, defines an expanded vitality. This is a form or expression of aliveness that carries listening further, against the enclosures of colonial-capitalistic capture, that work at systems of violence that proceed by cutting against the inherent ‘inseparability’ marking relations without relating.

The other-other held by way of (negative) listening puts one in touch with the unrecognizable, the nonhuman, the dead, the spirits; while listening assists in deepening a social bond, it is equally extending what counts as recognition. To relate without relating, as Ettinger suggests, is to sense precisely the limits of the familiar, and of oneself. Such limits point to the outside that Moten also intuits as fundamental to poetics. As he suggests, the fugitivity of poetics comes to destitute the fixed order of things, weakening borders (of communities, of languages) by way of gestures and enactments of escape, a freedom of thought, imagination, of embodied life, thereby opening onto an outside. That is, poetics tends to the outside, to seeing life in the object, to keeping attentive to the buried, the erased, and to the ever-present potentiality of connection: to finding alliances with that which refuses enclosure. This is the scene of (black) aliveness Kevin Quashie describes, one that makes possible the imaginative figuring of (aesthetic) worlds which, in particular, challenge structures of antiblack, antihuman, antilife violence (Quashie, 2021).

A poetics of listening, as I’m concerned to suggest, may assist in turning toward the body as archive, figuring forms of carrying as a craft, one that takes the limits of recognition expressed in relations without relating as the basis for an ethics, a style of existence. Such an ethics moreover assists in finding ways of inhabiting the outside, or what I may term the outer-outside: to become a listener in ways that open the sensible toward the disappeared, the erased, the echoic worlds of memory, and how it is we may carry original wounds.

A poetics of listening is positioned as operative to working through what troubles individual lives; it assists in attending to the unspeakable, finding ways of navigating the traumas and injuries that occupy communities, nations, histories – to listen into and with the emptiness as a type of negative labour so as to find orientation within the terrible expanse of grief, uncertainty, loss. By way of listening we may learn the languages of silence, and the silenced, we may recognize where recognition fails, is strained, where the other-other demands a logic of poetics; we may also know of the body as archive, as what is always involved in an exterior greater than ourselves, the outer-outside, and within which new resources may be found, foraged, and alliances constructed. Moreover, we may elaborate a language of witnessing as well as repair by way of a grammar of animacy, which is a poetic form of knowing, of moving with aliveness as radical flourishing – a ‘biopoetics’ which, as Andreas Weber suggests, challenges the prevailing logic of necropower (Weber, 2019, p. 77). To be a witness to oneself and others is to not only face the present or past, it is to listen out for the hidden and erased, the silenced and missing, as guides toward another form of survival. It is along these perspectives that witnessing is never solely a question of finding truth; rather, as Kelly Oliver importantly argues, witnessing enables ways of rebuilding subjectivities and the stories that come to carry communities (Oliver, 2001). It is a commitment to maintaining the dignity of lives, to carry even when there is seemingly nothing to hold.