How far do acoustic waves really reach? Do they stop at the faintest vibration of the eardrum, or do they extend into ranges that bypass the ear yet pulse through the body, provoking non-acoustic – uncanny – sensations? This chapter begins with the technoscientific fascination with infrasound and ultrasound: frequencies below and beyond the limits of hearing, whose effects on the human body and nervous system have been mapped, theorized, and, at times, weaponized. In parallel, I trace the emergence of a technological ontology of sound – one that detaches sound from the spectrum of audibility and situates the individual within a broader metaphysics of waves. In that sense, the study of sound becomes a lens through which to understand communication technologies and the concept of acoustic space, as developed by Marshall McLuhan (2004). An ‘ecology of waves’, it recasts listening as a metaphor not for hearing but for information: the realm of affect and the senses. The identification of infrasound and ultrasound is inseparable from the search for the outer borders of hearing – experimentation at the liminal point where pitch and amplitude lose their sonic connotations and become vectors of sensation. There are sounds that soothe and sounds that burn; and there are soundless vibrations yet classified as sound. This chapter explores the technoscientific (re)search into (un)sound objects and the use of such research for intelligence and military operations.1

The Unsound and the Spectrality of Bodily Responses

Epistemologies are not isolated domains. They are constantly reshaped by available technologies. In turn, they bleed into adjacent areas of knowledge, which carry their own – often conflicting – predispositions and political priorities. Interest in the unsound reflects this dynamic, as it is within the framework of its critical inquiry that we can retrospectively examine its experimental applications. This dynamic interplay between epistemology and technology is particularly evident in the emergence of the unsound as a critical object within sound studies. The interest in the unsound has developed in the context of the ‘ontological turn’ (Cox, 2011; Kane, 2015; Thompson, 2017) that has characterized the last two decades. This turn stems from a broader problematic that conceives sound not merely as a (cultural) product of hearing – speech, music, noise, or soundscape – but as a ‘vibratory event’ (Ernst, 2016, p. 24), a ‘vibratory continuum’ (Schrimshaw, 2013, p. 43), or a ‘vibratory force’ (Goodman, 2010, p. 81): an oscillating waveform with a rhythm or frequency such that it resonates with the tympanic membrane. Here, ‘sound’ ceases to be a product of the acoustic organ or an external source of vibration, becoming a rippling in air pressure that may or may not resonate in the tympanic membrane – either because of the pitch of the frequency (Hz) or the intensity of the pressure (dB). The spectrum of audibility is thus opened up to the contingency of the coupling between membrane and wave. Some may hear more – or less – than others. Indeed, in my opinion the interest in sound would not have shifted in this way had the technosciences not experimented with the limits (and at the limits) of its spectrality. ‘This is a necessary starting point for a vigilant investigation of the creeping colonization of the not yet audible and the infra- and ultrasonic dimensions of unsound’, says Goodman (2010, p. xvi), essentially opening up the question of the relationships between sense organs and the environment; technoscience and wave manipulation; sound, listening and warfare.

The unsound refers to all those frequencies that lie beyond the physio-logical range of audibility, typically below 20 Hz or above 20,000 Hz; frequencies that affect the body and the auditory system not through hearing, but through tactility, affect, and neurology. Not all inaudible frequencies are impactful. Nor are all impactful vibrations necessarily unsound. Rather, the unsound becomes a conceptual category – a heuristic device that directs research interest on the bodily dimensions of sonic experience, encompassing ‘all manner of synaesthetic interplay, misperceptions, microperceptions and other sound-like events’ (Jasen, 2016, p. 35). It thus gestures toward a broader field of vibratory phenomena that challenge the epistemological boundaries of sound. The spectrality of listening refers here not only to the frequency range of audible sound but to the ghostly, elusive nature of sonic phenomena. The study of sound thus becomes a study of potential bodily responses to stimuli that cannot be precisely identified – stimuli that are invisible or inaudible, that may elude representational systems; and that may be derivatives of technical infrastructures or fictional constructs (see Voegelin, 2014; Schulze, 2020). While some unsound events resonate with the body, others remain imperceptible, speculative, or infrastructural. Yet, they still exert force within cultural, technological, or political domains. In contexts such as intelligence and military research, the study of the unsound becomes part of a techno-politics of the environment – an ontopolitics of power (Chandler, 2018) or what Massumi (2015) coins ontopower: a mode of governance that does not exclusively target the subject (through discipline, normalization, or imposition), but the conditions in which the subject or populations live; it becomes part of a strategy that penetrates human ecology.

In a similar study of how sound systems can influence, manipulate, and torture, Heys (2019, p. 2) apprehends sound as air pressure; he observes that ‘as waveformed strategies become more abstracted, [...] the virtual nebulosity of both their technical possibilities and their online existence […] comes to reflect the ideational spatiality within which unsound (ultrasound and infrasound) operates’. As sonic technologies become increasingly abstract and speculative, they begin to mirror the conceptual terrain of the unsound itself. The unsound ceases to be just and only a frequency range; it is reconfigured as a discursive and affective space shaped by both technical innovation and cultural speculation. The study of sound becomes a study of spectres. Yet, simultaneously, it evolves into a technoscientific investigation of the spectre/spectrum of sound, which is itself a normative inquiry operating at the limits of the feasible and the spectral. This is the work of AUDINT (Goodman, Heys and Ikoniadou, 2019) which engages with the unsound in an ironic and speculative mode, exploring frequencies beyond the range of human hearing and their potential to modulate psychological and physiological states. Similarly, I begin with examples of experimental associations between sound and the body, technology and listening, as articulated within experimental investigations of the unsound, acoustic waves and the manipulation of human ecology. My aim is to interrogate the (onto)politics that render listening – and other forms of sonic exposure – not merely affective, but potentially dangerous, even life-threatening. In doing so, I trace how speculative sound becomes a vector of control, manipulation, and resistance within human ecology.

Spectres of Sound

A series of experimental investigations into sound has become a sensation among scholars of sonic warfare, not so much for its results but rather for the imaginative nature of its working hypotheses and especially for the way it straddles the line between science and metaphysics. These experiments formed part of an effort to debunk allegedly proven paranormal phenomena by attributing their characteristics to the properties of sound. In a 1998 article, engineer Vic Tandy and psychologist Tony Lawrence – both researchers of the paranormal – explain how sound can induce feelings of depression, heighten discomfort, stimulate anxiety, and even cause visual distortions (Tandy and Lawrence, 1998). For them, as investigators of the paranormal, such sensory phenomena often manifest as ghosts, hauntings, or other supernatural experiences. Their aim, however, was to interpret such unexplained occurrences through a scientific and technical lens. One such supernatural experience led them to investigate a medical equipment manufacturing laboratory, where Tandy worked as a machine designer. Colleagues frequently reported unsettling yet inexplicable sensations: waves of melancholy, sudden chills, and fleeting impressions of an alien presence. Tandy speculated that it might be due to ‘some piece of equipment wheezing away in a corner’ (ibid., p. 360). In the article, Tandy appeared well-acquainted with such uncanny phenomena, and even more so with their physico-technical explanations. Strange noises, for instance, might stem from contracting water pipes; mysterious phone calls and TV signal interruptions could be traced to electrical malfunctions. Unexplained draughts and damp patches in a house often result from poor construction. Even hallucinations, he noted, might be triggered by electromagnetic anomalies. These are among the most trivial explanations offered for phenomena that, at first glance, seem exotic or otherworldly.

As in other cases of experimental research based on sound, it was Tandy’s personal experience that led him to investigate this apparent supernatural phenomenon more closely. He had occasionally found himself alone with all the equipment switched off, ‘sweating but cold’, with a feeling of ‘being watched’ and an eerie ‘chill in the room’, convinced that ‘something was in the room’ (ibid., p. 361). He would look around, searching for a cause, even checking for possible leaks in the anesthetic bottles. One evening, while alone in the laboratory attempting to repair a fencing blade, the blade – resting in the vise – began to ‘frantically vibrate’ (ibid.) of its own accord. It was then that he concluded that the blade was receiving some kind of kinetic energy and decided to investigate more closely the technical causes of his discomfort. Interestingly, the two researchers identified the change in the workers’ psychology, their uncanny impressions, and the inexplicable oscillation of a foil blade with the same mechanical energy that was ‘invisibly’ circulating between them. And indeed, they ‘discovered’ the presence of a standing acoustic wave at 18.98 Hz. In fact, this discovery was made not with the aid of a special microphone or other sophisticated equipment, but simply by empirically locating the point at which the blade vibrated most strongly and applying the frequency equation (speed of sound divided by wavelength). By assuming the wave was stationary (i.e., a wave whose maximum height does not move in space, resulting from two identical waves travelling in opposite directions due to reflection off the room’s walls), they did not only find the height (essentially the amplitude) of the frequency; this was 19 Hz – the threshold of audibility. They also determined the actual cause of these strange paranormal phenomena. The evidence supporting their conclusion came from the laboratory foreman, who testified that a new fan had recently been installed in the extraction system at the far end of the laboratory. And indeed, when they turned off the fan, the eerie presences disappeared.

Assumed conclusions, speculative interpretations. Yet the boundary between science and mystery remained porous. A year later, the same engineer began an investigation in the cellar of a 14th-century building – the Tourist Information Centre in Coventry, UK – reputed by caretakers and visitors to bear traces of paranormal activity. By then, Tandy had become a recognized figure in the realm of ‘ghost hunting’ and the debunking of paranormal phenomena with his theory on the sensory effects of infrasound frequencies (Baker and Bader, 2014). He had even equipped himself with a new team and the necessary hardware to probe the room’s secrets, to listen to silence – hoping it might speak in vibrations, in frequencies too low for the ear but not for the body. And despite identifying several elevated subsonic regions (including 19 Hz), the absence of a distinct frequency peak that could offer a clear explanation (as in the laboratory case), and his inability to trace a source of infrasound (such as a ventilation system), did not deter Tandy. He vigorously proclaimed the significance of the 19 Hz frequency in producing uncanny impressions. In the aftermath of these investigations, a substantial body of research into paranormal phenomena emerged. Even though most of it aimed at challenging Tandy’s speculations, all research was attentive to the possibilities of infrasound, particularly its potential interaction with electromagnetic waves and other physical forces (Braithwaite and Townsend, 2006; French et al., 2009; Parsons, 2012; Mühlhans, 2017). In all cases, gloomy feelings and haunting impressions – unreal, inexplicable – were traced to stray signals and leaky waveforms, ghostly remnants of unseen forces. Perhaps such an example would pass unnoticed, were it not for the quiet presence of an implicit ontopolitics: one that not only recognizes the entanglement of human presence within its environment, but also dares to seek and experiment with the intricate relations of complexity that shape and unsettle it.

Sonicity, Acoustic Space, and a Geography of Signals

Since the early modernity and the scientific study of acoustics, the mechanics of sound have been separated from the phenomenological manifestations of audibility. This scientific paradigm foregrounded the physical properties of sound, such as wave propagation, reflection, and absorption, while mapping its transmission through anatomical structures in increasingly precise, mechanistic terms. ‘The ear was a destination of sound waves’ (Sterne and Rodgers 2011, p. 46): an assemblage of discrete organs (such as the pinna, the eardrum, the cochlea) within which waves transition and develop into the quasi ‘hallucinatory’ effect of hearing (Bonnet, 2016, p. 166). Sound, then, does not exist as a product of listening, but as an oscillation of air pressure, as a mechanical wave. Such a notion is ab initio alien to the auditory experience. For ‘listening is always listening to something; and this is always a function of a given [social] situation’ (Ibid., p. 76): listening implies the activation of a reflexive process with the environment on the part of the listener.

Treating sound as ‘fluid disturbances’ in the air and as ‘vibrating particles that voyage back and forth’ (Sterne and Rodgers, 2011, p. 45), ‘liberates’ sound from acousticity. It places it within a techno-logic of the wave in terms of amplitude, frequency, and spatial direction. In other words, oscillating air pressure as wave could be visualized, delineated, reproduced, modulated in amplitude, frequency, and pressure ratio, and mathematically designed for purposes spanning scientific fields as diverse as aerodynamics, meteorology, electricity, and telecommunications. Indeed, it is not surprising that Thomas Edison invented both the phonograph and the electric light bulb, and that Heinrich Hertz, the person who gave his name to the unit of frequency, made possible both the emission of radio waves and the foundational architecture of acoustics. As sound entered the domain of electrical and mechanical systems, its identity was reshaped from a phenomenological event to a technical entity within emerging infrastructures of communication. If sound was ‘separated’ from hearing, then, it was not in the sense of loss, but of its elevation to a derivative field, manifested or activated through signals, circuits, and the transmission of information (see Sterne and Rodgers, 2011; Erlmann, 2017; Greenspan, 2019).

In this novel metaphysics of waves, the differences between mechanical and electromagnetic waves do not seem to matter much. Rather, it is the similarities in their behaviour – in terms of amplitude, wavelength, frequency, velocity, phase, and reflection – that ‘elevate’ the ear to a privileged centre for the sensory perception of the environment and that seem to have led McLuhan (2004) to the concept of acoustic space as a key epistemological field of information technologies (Ernst, 2016, p. 25). For McLuhan, unlike visual space, acoustic space has no centre, no fixed direction, and no discrete boundaries, except those situationally occupied by the listener. Acoustic space arises from the same conditions of automatic development and direction of acoustic waves; that is, it is a place inhabited by constantly pulsating (responsive) relations between oscillating flows, open to the potentiality of incoming reflections. Ernst employs the term sonicity (ibid., p. 21) to describe sound not as something necessarily audible or acoustic, but as a signal, a vibration – temporal, and media-technical by nature. Once severed from audibility, the acoustic wave unfolds according to its own physical mechanics, within a metaphysics of waves. In this framework, sound becomes a signal-based transition, propagated through a medium, which is now capable of being registered, stored, and processed by technical apparatuses. Thus, the notion of sonicity encompasses electromagnetic vibrations, digital signals, and other non-audible events and phenomena that share the structural and temporal properties of sound. This is where, for McLuhan, sound becomes synonymous with electricity. By enabling the human sensorium to form autonomous synapses with its environment – beyond and in continuity with the skin – acoustic space becomes a matrix of communication. It provides the mechanisms for extending and extrapolating the human nervous system to radio, television, and computers – all those electronic devices that McLuhan considers prosthetic machines.

In the technological realism of acoustics, listening becomes a metaphor for both sound and information. It becomes a metonymy for receiving and decoding the signals of the environment, with sound being the stimulus par excellence in this human ecology. Similarly, the body becomes both a mnemonic device – an archive of experience mediated by technical means – and an affective resonator in which externality and interiority infold together. The body is cellularly assembled to the fluctuations of its surroundings, maintaining a privileged relationship to media, devices, and derivative (virtual) interfaces. For Hulbert (2020), the ability to fold and upload signals across different planes through technique has enabled the strategic demodulation of sound into economies that augment, enhance, or add to the surrounding qualities of the experience of the acoustic space. Thus, if sonicity is not confined to the acoustic experience, it is because it becomes a means of geographizing this new ecology. Sound isn’t just heard. It is engineered, interpreted, and woven into the fabric of how we live and feel. Detached from the ear, listening has become a stake in the architecture of communication technologies, and audibility has become more than what can be heard. Assembled within signal-based apparatuses, it has become a spectrum whose limits are measured in degrees of silence, affective engagement, and spatial attention. It is in this realm that ‘fear’, ‘melancholy’, and ‘uncanny impressions’ meet the vectors of technological devices, the regimes or structures of sonic enclosure (like cinema or the Walkman), and the fantasy of manipulating the body – let alone perception – through frequencies or sound waves.

Targeting Audibility

Another incident, akin to the case of Tandy and Lawrence, has also captured the attention of scholars of sonic warfare. Around 1965, at the height of the Cold War and the international arms race, Russian robotics engineer Vladimir Gavreau and his colleagues (working within the French military industry) experienced similarly unpleasant physical disturbances when a ventilation system was installed in a neighbouring building. At the time, the team was already engaged in developing weapons systems, specifically remotely controlled mobiles and robotic devices for industrial and military uses. When they began to suffer recurring symptoms such as nausea and migraines, they took it upon themselves to investigate the causes of these collective ailments. ‘We had the impression that our heads were going to burst, and it soon became unbearable’ (Volcler, 2013, p. 25), Gavreau had reported. Given their work in military facilities, the team took the phenomenon seriously and initiated a series of biological and chemical investigations. Only when they noticed that the symptoms diminished after some laboratory windows were closed, were the building’s engineers able to identify the true cause: a loosely mounted low-speed motor, situated in a cavernous duct that acted as an infrasonic amplifier. According to Gavreau (ibid.), ‘The intensity of the infrasound was so strong that everything vibrated: tables, glassware on the tables […] curious patterns appeared on the surface of liquids. Even the needle of an ordinary barometer oscillated’. When they finally managed to measure the exact frequency, they found a magnified peak at 7 Hz. They also discovered that closed windows altered the building’s total resonant profile, shifting both the infrasonic pitch and intensity, thus minimizing the effects (see Vassilatos, 1996, p. 31).

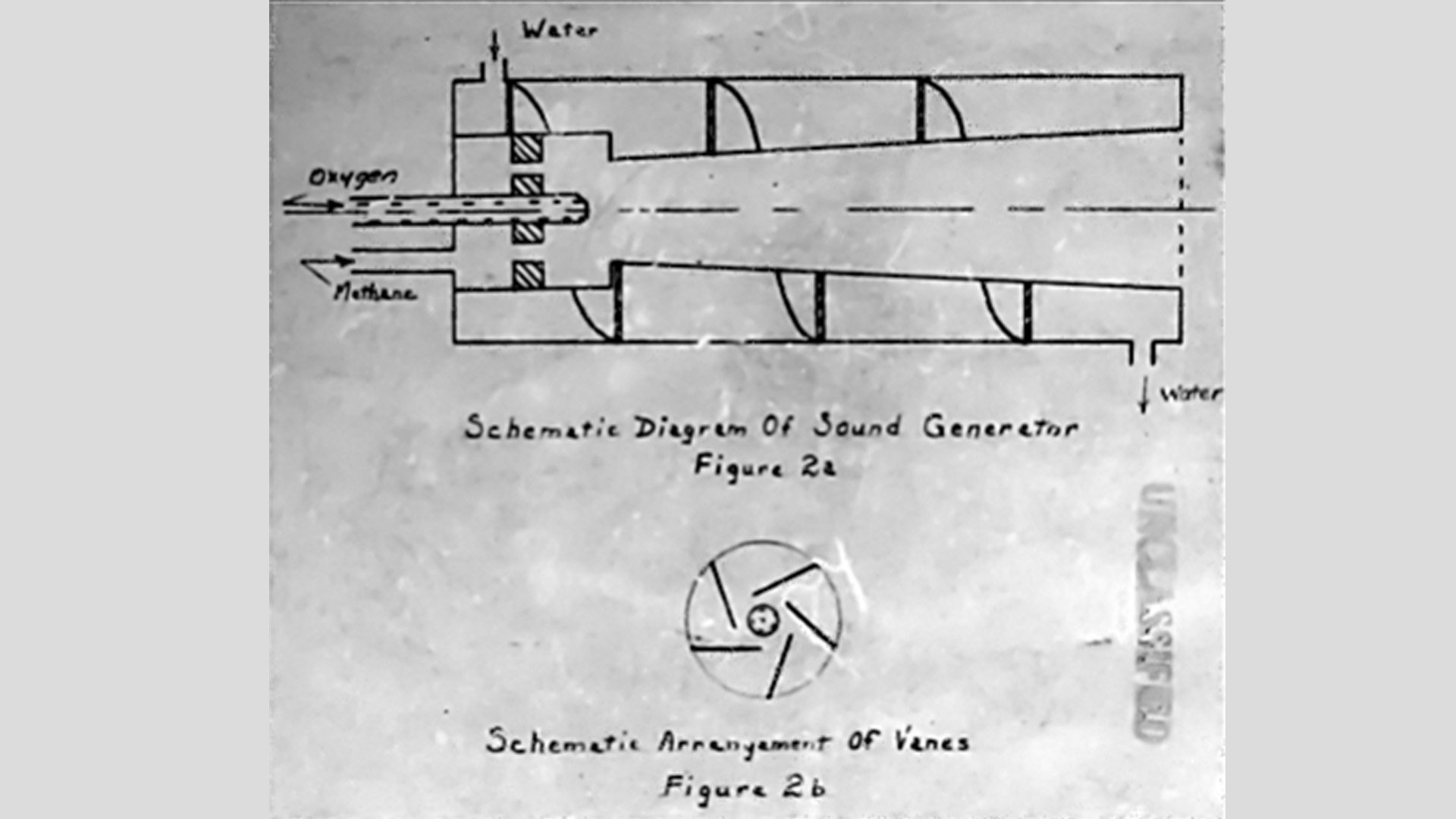

Upon making these discoveries, Gavreau and his team began experimenting with infrasound, sources of vibration, and their effects on the human body, aiming to weaponize them. Interestingly, their initial designs closely resembled the structure of the ventilation system they had identified as the source of the original vibrations. To replicate the same 7Hz frequency, they constructed a concrete pipe, 24 meters long and two meters in diameter; essentially a kind of sound cannon said to render ‘the most simple intellectual task impossible’ (Volcler, 2013, p. 26). In another device, which they called an ‘acoustic gun’, they managed to emit 160 dB at 196Hz. Supposedly by ‘resonating’ with the internal organs of the body, it would strike them to the point of causing permanent damage. With a third device, they were able to emit a 37Hz sound signal with such intensity that ‘the walls of our laboratory began to vibrate and little crevices appeared!’; resembling a giant whistle, the device was one and a half meters in diameter (ibid.). Amid speculation about the physical effects of such frequencies, and buoyed by their enthusiasm for the results of their constructions, the team eventually abandoned the experiments. None of the devices worked as intended. They were forced to stop due to the disruption they caused: specifically, the researchers’ inability to contain the sounds, which spread into neighbouring buildings. Ultimately, the sheer impracticality of such devices – unwieldy in both construction and control – rendered further experimentation unfeasible.

What remained were more questions than answers, a myth gathering around Gavreau’s name and the supposed perils of infrasound, igniting a lingering debate over its elusive physical effects (see Altmann, 2001, p. 227; Davison, 2009, p. 189; Volcler, 2013, p. 27–28). Gavreau would later concentrate on developing mechanisms for shielding against infrasound (Bowdler, 2018, p. 283). Indeed, perhaps the most promising goal of these otherwise mythical experiments was to produce infrasound that was also directional (see Volcler, 2013, p. 25); this feature would make sonic weapons usable, since they would not neutralize everyone within their range, let alone their operators. An ‘unattainable’ goal, as they were confronted with the ‘natural’ properties of low frequencies: their omnidirectionality, that is, the fact that they are emitted in all directions.

These failed experiments do not merely mark the limits of technological feasibility. They expose a deeper misunderstanding of sound itself, not as a force to be directed, but as a relational field in which listening is already embedded. Altmann (2001), Davison (2009) and Volcler (2013) have each undertaken substantive investigations into laboratory tests involving infrasound – military and otherwise. In their own ways, they examine a range of initiatives from research programmes and applied science centres in countries such as the USA, the UK, the Soviet Union and later Russia, as well as China, focusing on prototypes primarily designed for maintaining order, crowd control, and military defence. However, all three authors conclude that experimentation on the offensive use of infrasound is impractical or unrealistic, affirming the impossibility of producing acoustic weapons based on infrasound or low frequencies. In fact, these scholars adopt a pragmatic – even mechanistic – approach, not unlike that of engineers in applied science centres: they seek to determine whether it is truly feasible to build a weapon that fires infrasound. Yet in doing so, their debunking of such claims simultaneously contributes to further fetishization. Namely, if this is the case, why, then, does research into the weaponization of infrasound persist despite all evidence to the contrary?

The unsound is inextricably tied to audibility. Infrasound lies at the margins of listening. What, then, is listening? And how does it become the stake of an offensive politics? Listening speaks, says François Bonnet (2016, p. 140). Seeking to place the auditory experience in a reciprocal relationship with the environment, neither does he treat sound as an objective event nor listening as a purely phenomenological sensation. Listening ‘speaks’ in the sense that sounds are grasped within the open horizon of an aestheto-fictional register. It is the constantly receptive energy of listening that makes sound speak, carrying a communicative value that exceeds discourse. Therefore, listening speaks for the sound it captures. Such a conception of auditory experience reveals the indexical function of listening; it exposes its self-referential character. Sound does indeed develop in the field of the listener’s existence and not in the world as such. But the fact that ‘listening speaks’ also reveals the permeability of the body, which becomes more apparent than anywhere else in the tympanic membrane, the ear, which is always open as a permanent receptor – autonomously connected to the waves of the environment at the cellular level.

If listening speaks for the sounds it captures, then from the part of the ear, the world is nothing but sounds waiting to be realized. To articulate dangerous frequencies, then, is to interfere destructively in this mutual association. It is to provoke an unbearable reception. For experiments such as Gavreau’s, failing to enter into the environment’s relations of complexity, end up merely aiming to push the pressure of sound waves to the limits of what the ear, or even the body, can tolerate. And if the results of such experiments have remained at the level of anecdote – mythical endeavours in pursuit of otherwise unattainable goals – it is because they fail to recognize the folding dimension of auditory stimuli, mistaking ‘objective events’ as leading linearly to ‘subjective affects’. The ear does not merely receive acoustic energy. It participates in an ecology of waves. And sound is not only air pressure. It is ripples in the fabric of the environment that encompasses and folds around and into listening entities. Low frequencies are indeed non-directional, but not because of their ‘physical properties’, but because of the relative position of the listening subject in a space of constantly flowing mechanical waves. Those with higher frequencies in the audible spectrum produce the (necessary yet always illusionary) auditory effect of movement and directionality of things due to the distance between the ears.

Beyond Acoustic Experience

There is one programme within the CIA’s MK-ULTRA behavioural modification project that deserves particular attention here: Subproject 54, initially studied by the US Navy before the CIA assumed control of its funding. Little is known about the methods, conditions, or outcomes of the experiments, as all records were allegedly destroyed. The only remaining information comes from the Joint Hearing Before the Committee on Intelligence. During the hearing, Senator Schweiker requested details about the project, which ‘involved examination of techniques to cause brain concussions and amnesia by using weapons or sound waves to strike individuals without giving warning and without leaving any clear physical marks’ (US Senate 1977, p. 40). After initially denying involvement in the programme, the CIA acknowledged its participation, without providing further details. These keywords remain: brain concussion, sound waves, no physical marks. During the 1990s, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) – a US government agency credited with innovations like the ARPANET, GPS, stealth technology – initiated the Hello, Goodbye, and Goodnight projects. The aim of these was to study how to modulate the fluid of the inner ear by microwave heating to produce a devastating clicking or buzzing sound within one’s head – for crowd control or military defence, depending on the project (Mai, 2022, p. 328). There is another microwave-based weapon, the so-called MEDUSA (Mob Excess Deterrent Using Silent Audio), similar to the above. Funded by the US Navy, it is perhaps the only one that was publicly announced in 2003. Again, the device was designed to create this specific microwave auditory effect – the Frey effect, or ‘silent audio’ – to induce the sensation of a painfully loud boom, or to disrupt balance, cause fever, and trigger epileptic seizures (see Krishnan, 2016, p. 121; Mai, 2022, pp. 330–331). Together, these three programmes reflect a growing interest within US defence research in weaponizing sound and electromagnetic energy. Yet, all appear to have been halted, likely because they ultimately strayed from the criteria of ‘non-lethality’, harbouring the potential to cause serious or even permanent neural damage.

The exact capabilities of these weapons remain the subject of rumour and speculation. Volcler denies their practicality and effectiveness citing the absence of credible test results. However, this line of reasoning is increasingly untenable, for as Krishnan admits (2016, p. 120), ‘these weapons are generally shrouded in secrecy’. The unwillingness to disclose relevant information is not unrelated to the reported development of electromagnetic weapons by Russia and China. Russia, in particular, is considered a pioneer in this field, with its interest in using electromagnetic waves for mind control and crowd control, dating back to the early days of the Soviet Union (see Velminski, 2017). Recent incidents have provided serious indications of the use of this type of weaponry. The most well-known case occurred in 2016 in Havana, Cuba, where US embassy officials suffered from headaches and piercing sounds en masse, without any precedent of such ailments (see Popli, 2024). Subsequent medical investigations identified the acute onset of neurological symptoms, including loss of balance, dizziness, insomnia, and memory impairment. These were associated with perceived localized loud sounds, such as screeching, chirping, clicking, or piercing noises (see Asadi-Pooya, 2022; Conolly et al., 2024). The initial inability to determine a definitive cause led to the term Havana Syndrome, which was later reclassified as AHIs (Anomalous Health Incidents). Since that incident, several similar cases have been reported in Guangzhou, China, Moscow, Russia, Frankfurt and Berlin, Germany, as well as in Austria, Georgia, Taiwan, and even the USA. Those affected were primarily diplomats from the USA and other Western countries. In western public media, there is no mention whatsoever of psychological operations, diplomatic sabotage, or espionage. Instead, there is a persistent effort to downplay or dismiss any suggestion of Russian involvement in these incidents. But in military training documents, Russian involvement is treated as a given, with references to the use of either inaudible sound weapons (Nichols, 2022) or electromagnetic devices employing ‘silent audio’ (see Mai, 2022). All of these fall into the category that, in Russian military parlance, is referred to as ‘psychotronic weapons’, an integral component of 21st-century neurowarfare (Krishnan, 2016, p. 12).

To speculate theoretically does not mean attributing objective value to assumptions based on imaginary correlations. Rather, it involves recognizing the horizon of possibilities opened up by emerging technologies and theorizing events of interest as potential assemblages. Thus, speculating on incidents like the above does not entail taking them for granted; but it does require acknowledging them as potential realizations in a new terrain whose strategic necessity we are only beginning to discern. Hence, the reason I highlight research on silent audio, or the case of Gavreau’s research team – let alone that of Tandy and Lawrence – is not to mystify or fetishize the idea of bloodless yet deadly-effective ‘ethereal’ strikes. On the contrary, while such cases may reflect a fascination with sound-wave applications, clandestine sciences and secret weapons, I mention them because they point to the broader scope of the quest for the unsound, which extends beyond the spectrum of audibility, opening up the horizon and phenomenology of acoustic waves. This concerns the directionality of movement; the localization of objects; the ability to balance; kinesthesia and the sense of gravity; the perception of space and orientation in an environment. These are all part of the functions of the ear and, in particular, of the inner ear, the so-called labyrinth, which simultaneously modulates mechanical air waves into electrical signals and provides real-time bodily directionality in an environment of waves. This is the true field of operation for any weapon designed to induce nausea, fear, disorientation, distress, and other psychotropic effects. The fact that there exist radio-wave or other electromagnetic-based weapons that target the inner ear is indicative of how ‘sound’ has been detached from audibility. Indeed, in such cases, there are no mechanical vibrations in the air, only direct vibration of the fluid within the inner ear, as if the subject were made to actually ‘hear voices’.

The Ontopolitics of ‘Non-Lethal Weapons’

In any case, and despite the justified demystification of acoustic weapons by researchers investigating the use of sound in torture and warfare, sonic weapons indeed do exist. The directionality of infrasound and low frequencies is now considered feasible (see Vaisman, 2001, p. 26). Ultrasound is used in medicine not only to image internal organs but also to ‘sublimate’ – that is, to burn – cancer cells or break up kidney stones. Air pressure can be modulated by vortex cannons, which shoot rings of air with enough intensity to take out a target at a distance of 50 meters; these devices are being used experimentally in agriculture to break up hail clouds.

There are piezoelectric loudspeakers that can direct sound waves by emitting narrow beams of ultrasound – soundless high-frequency waves that act like mechanical levers in the atmosphere, modulating vibrations in the audible spectrum to produce the final effect of sound.2 Such loudspeakers include the well-known LRAD used by regular armies and security forces to control and disrupt crowds, as well as ‘the Scream’ also known as ‘The Shout’ or in Hebrew Tze’aka which is used by the Israeli Defense Forces for the same purposes (Bowdler, 2018, p. 284). Similarly, in the 1970s, there was the so-called ‘squawk box’, allegedly used by the British Army during riots in Northern Ireland. It reportedly emitted simultaneous ultrasound frequencies of around 30,000 Hz and infrasound frequencies of 2 Hz – a weapon whose existence has been officially denied by UK governments (Davison 2009, p. 189; Volcler, 2013, p. 29–30). There are also sound repellents designed specifically for teenagers, such as the British company Mosquito’s security system, which emits high frequencies around 17,000Hz – highly irritating, but which human neurophysiology is unable to detect after the age of 20–25, and therefore inaudible to adults (Maher, 2016). Additionally, there are microwave-based systems such as the ADS (Active Denial System), which can burn the skin of its target by emitting microwaves from a distance of up to one kilometre (Mai, 2022, p. 326). And of course, there is MEDUSA, which produces silent audio – an acoustic effect first observed and experimented upon in the 1960s by the physicist Allan Frey (Krishnan, 2016, p. 125).

All these devices are occasionally shrouded in mystery, especially when their public exposure coincides with civilian reports of unexplained injuries allegedly caused by unknown weapons. Since the 1990s, following the end of the Cold War, research into the military use of sound – and the debate surrounding it – has multiplied in the search for smart, undetectable, and even imperceptible weapons. Vaisman (2001) observes that this has to do with the changing status of the USA after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. ‘The military wanted weapons that reflected the US’s new international role’, she notes, explaining that this role included targeted military intervention, urban riot control and intelligence gathering (ibid., p. 25). In this new context of ‘peripatetic interventionist’ activity (ibid.), the US invested in a new class of weapons termed ‘non’ or ‘less-lethal’ weapons; this class did not aim to permanently and fatally neutralize targets, but rather to partially and temporarily disarm them, minimizing the possibility of permanent damage (Fidler, 1999; Casey-Maslen, 2010; INCLO and PHR, 2016). In addition to acoustic weapons, these include: biological weapons; tranquilizers, hallucinogens, bacteria and chemical agents that cause corrosion, super-adhesion and super-combustion; electrified water cannons; multispectral smoke grenades; flash guns; stun nets; swelling foams for fortification and blocking; lasers; non-nuclear electromagnetic pulses and other electrical signal inhibitors; electrified weapons, and other microwave weapons (see Davison, 2009). Military industry investment in this wide range of ‘non-lethal weapons’ was supposed to be ‘the humanitarian antidote to atom bombs’ (Vaisman, 2001, p. 25).

The 1990s were indeed crucial for the demarcation and inclusion of acoustic weapons within a category that both subordinated and politically legitimized them. This development cannot be viewed in isolation from the proliferation of information technologies in the public sphere and the transition of Western – and more broadly developed – societies into what Gilles Deleuze (1992) refers to as Societies of Control. The rise of ‘humanitarian’ weapons responded to a political demand to discipline crowds within open and flexible systems for monitoring and regulating behaviour. The increased capacity of these new weapons for area control aligns with the growing need for continuous, pervasive, and technologically enhanced forms of governance that monitor and guide subjects and collectives. In fact, Volcler argues that the advantage of acoustic weapons was not necessarily its effectiveness compared to other ‘non-lethal’ weapons; on the contrary, their use was almost inseparable from the possibility of causing permanent harm. What made them politically viable was their ability to weaken criticism of the potential danger posed by these new weapons and to obscure the debate over what constitutes a ‘weapon’ and what ‘non-lethal’ truly means (Volcer, 2013, p. 1). The significance of the investment in acoustic weapons, she continues – apparently less ‘effective’ than water cannons, tasers, and tear gas – is that it heralds a shift in the perception of power, in law enforcement, in the management of the public sphere.

Aptly, Massumi (2015) notes that the governance of 21st-century societies increasingly resembles a military operation. As he explains, contemporary doctrines advocate a ‘full-spectrum force’ in which military operations extend into ‘grey areas’: that is, ‘areas formerly considered the exclusive purview of civil institutions’ (ibid, p. 67, 68). In this context, the use of information and misinformation, the stimulation of emotions, the arousal of passions, and the manipulation of the experience of time (in the sense of waiting, anticipation, exhaustion, and stress) become constitutive parts not only of warfare but also of the political development of ontopower: A ‘positively productive [power] for the particular form that a life will take next’ (ibid, p. 71) – a power whose military field of operation is the very environmental conditions in which both soldiers and civilians live. The military industry’s investment in acoustic technologies may not have heralded a tangible scientific leap – any more than directional sound or silent audio is ‘tangible’ – but it exemplifies 21st-century doctrines’ turn to ‘Operations Other Than War’ (OOTW), aimed at information control, spatial perception, confusion, fear, and disorientation.

Within Derived Economies of Acoustic Reception

Returning to McLuhan’s notion of acoustic space as the milieu for the emergence and development of information technologies, only to focus this time on the subject within that space. For sound, as noted above, functions in terms of information for the body as a sensorimotor organism. It does not merely function as an acoustic phenomenon but as actionable data: the body decodes minute pressure variations into kinesthetic and perceptual cues, sustaining an ongoing feedback loop with its surroundings. Within this epistemology of acoustic space, the subject is never hermetically sealed. It is dynamically tethered to ambient waveforms, its sensory tissues vibrating in unison with atmospheric oscillations. When these mechanical oscillations are captured and governed by signal-based communication technologies and fed into transmitter-receiver circuits, the subject effectively extends itself into an asymmetrical yet synchronized techno-sonic network, collapsing the boundary between organic and engineered sensory nodes. ‘Sound and music allow us to experience transient time’, Ernst notes (2016, p. 22), explaining that sonicity does not concern merely auditory perception but mostly a temporal processuality, allowing to choreograph the body’s rhythms of movement, attention, memory, and affect. Auditory experience is equated with the bodily experience of time. In this sense, signal-based technologies produce temporalities, reify the collective experience of time, situate the sources and velocities of waves through their capacity for ‘simultaneity, superimposition, and nonlinearity’ (ibid., p. 36). If, on an epistemological level, the fantasy of acoustic weapons is fulfilled by information technologies, it is not in a manner of abstraction that would neutralize and paralyze the subject (as sound weapons would seek to do), but through the addition of layers of stimuli to the auditory system. Soundscapes are augmented with information, and spatial orientation is artificially adjusted through the mapping of movements, the monitoring of vibration sources, and the delineation of their morphology.

Volcler (2013, p. 21) notes that infrasound and low frequencies were the first to draw the attention of military and other covert research into the unsound because of their ability to resonate with the organs of the human body. Yet they proved even more significant, as they encompass the range in which the acoustic signatures of large machines – such as the ventilation systems in the Tandy and Lawrence cases and those studied by Gavreau’s team – are left. The mechanics of infrasound (<20Hz) and low frequencies (20–160Hz) do not appear complex at first glance. Low frequencies are generated by mechanical energy transmitted to a medium (in gaseous, liquid, or solid form) by large-scale motions such as ocean waves, earthquakes, volcanoes, and extreme weather events (such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and high winds). Whales, octopuses, elephants, and other mammals are also known to use infrasound to communicate over long distances. This is because low-frequency waves take several meters to complete a cycle and become audible, so they travel long distances before their intensity fades, passing through many material obstacles without being reflected. Humans can hear infrasound if the Sound Pressure Level (SPL) is high enough (>120dB). But even if it is not audible, infrasound, as already implied, is felt by humans. Goodman notes that infrasound escapes perceptual registers, producing anxiety and fear precisely because of the absence of a specific conscious cause; and that affect has developed automatisms on these relations, specifically ‘the fight, flight, and freeze responses’ (2010, p. 66). It is from these bodily responses that research and fictional speculation on the unsound and its transformation into a weapon have begun.

Once more, a dispassionate and sober reading of the history of infrasound would recognize that its significance lies in the vibrations emitted by objects, the detectable pulses produced in real-time by others, in the distinctive acoustic signature they leave. Long before acoustic weapons entered experimental use, devices for tracking and recording infrasound – subsonic radars – were already in operation. At an epistemological level, the production of infrasound-based acoustic weapons is no different from the creation of passive subsonic radars: in the first case, the articulation of dangerous, soundless frequencies; in the second, the covert listening to silent movements. In both instances, the calibrated management of air-pressure intensity for intelligence gathering and military operations marks a transition to an ecology of waves. It is not surprising that so little importance is given to the detection, tracking, and object characterization for military purposes in the study of unsound. Paradoxically, the answer is simple: the mystification of subsonic weapons overshadows all research on the military applications of infrasound.

In the metaphysics of acoustic space, everything flows and communicates through autonomous mechanical connections. Just as in meteorology, ecology, biology, and other environmental sciences, cybernetics becomes a way to study communication and feedback loops between various materialities, organisms, and different class systems, so too in acoustic space, sensors, signal processing, and monitoring through automatic adjustment serve as tools of engaging with the relations of complexity shaped by continuous and inter-colliding reverberations. Subsonic radars detect the movement of objects by receiving inaudible acoustic energy as externally instituted instruments of sensory perception. The ‘subject’ itself becomes dispersed – or rather, the organs through which the subject processes the temporal experience of the present are partitioned and radiate outward. As acoustic space comes under the governance of external devices (microphones, loudspeakers, radio transmitters, radars), human perception is progressively subsumed into a derivative economy of reception. In this economy, additive mechanisms of signal modulation and amplification, filtering and projection, attune us to circulating currents of speculative auditory stimuli. Resonances of virtual or derivative sources, they shape both what we hear and how we sense our own presence within an engineered soundscape.

Towards a New Economy of the Unsound in Warfare Strategy

It is not only earthquakes and cyclones that generate low-frequency mechanical energy. Many other mechanical movements also produce infrasound. Wind turbines, diesel engines, the propellers of ships and submarines, the sonic booms of fighter jets breaking the sound barrier, explosions, tank tracks, and rocket launches are all sources of infrasound; this fact has not gone unnoticed by the military. Since the very first recording of infrasound during the eruption of the Krakatoa volcano in Indonesia in 1883 (whose shockwave is said to have travelled seven times around the earth), the firing of weapons has been one of the primary areas of military research into infrasound (Mühlhans, 2017, p. 6). As early as the beginning of the 20th century, at the peak of the Technological Revolution, attempts were made to locate firearms, trains, and submarines using sound-ranging – ‘the simple idea to triangulate sound with at least two sensors by its time lag’ (ibid: 7); in other words, to locate the position of a sound source by analysing the differences in the time it takes for the sound to reach at least two spatially separated sensors. In World War I, many devices were used for this purpose, attempting to simulate a giant ear. The Japanese ‘war tubas’, the French ‘paraboloid of Baillaud’, the German Richtungshörer or Wertbostel, and the British ‘acoustic mirrors’ are just some of the so-called acoustic locators that pioneered the detection of planes and tanks during this period. Nowadays, such instruments are presented as exotic devices from an outdated technological era, despite the fact that it was the mechanics of signal processing, real-time feedback, and data integration that laid the foundations for the development of the electromagnetic radar and, thereafter, the science of cybernetics (Scarth, 2017, p. 390).

The development of electromagnetic radars during World War II did not render passive radars obsolete. The need for increasingly accurate and long-range early warning systems coincided with the shift to active radars, but their operation differs fundamentally. Electromagnetic ‘active’ radars operate via echolocation: that is, by emitting a signal and detecting an object through its echo, calculating its distance, direction, and speed based on time delay and the Doppler effect. Acoustic ‘passive’ radars, on the other hand, detect and analyse incoming mechanical waves from the environment. They determine the location of a source by measuring the differences in arrival time at multiple sensors. They stand still, passive. They do not ‘communicate’ with the source, but rather eavesdrop on its movement. Hence, they are completely stealthy as they emit no signal.

Indeed, these early acoustic/passive radar efforts at the turn of the 20th century were only the beginning of the development of a network for surveillance, monitoring, and intelligence of military operations and exercises around the world. Later, with the advent of the atomic age, it was the acoustic-seismic monitoring systems that took over, designed to detect the low frequencies generated by nuclear weapons testing conducted by rival powers. At the height of the Cold War, the US Navy developed the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS): a secret programme to monitor submarine movements in the Atlantic using arrays of hydrophones, covering the entire east coast, including Canada. The programme was declassified in 1991 after the end of the Cold War, marking the entry into the new ‘humanitarian age’ and the investment in ‘non-lethal weapons’. In this context and in accordance with the operating standards of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organisation (CTBTO), a monitoring system consisting of 337 sites around the world has been under development since 1999, using seismic, hydroacoustic, and infrasound technologies for exactly the same purposes. Every time North Korea is conducting a nuclear test, a sensor simulating a giant ear is installed somewhere to detect it.

Today, of course, military needs have changed considerably. The ‘peace regime’ of the 1990s and the global role of the USA shifted rapidly with the onset of the so-called War on Terror. Acoustic weapons have proven to be seriously hazardous; and in a 1999 memorandum, Human Rights Watch urged governments to review such technologies under international humanitarian law. Meanwhile the absence of a permanent adversary like the Soviet Union reduced the need for fixed surveillance systems. In the 21st century, submarine detection sensors are deployed on demand with portable floating stations, such as the USNS Able (T-AGOS-20) operated by the US Military Sealift Command. Many similar systems are being developed to detect, track, and classify anti-aircraft missiles on the battlefield, an ingenious way to eavesdrop on enemy defences in real time. In the Russian military, the PTKM-1R anti-tank mine is designed to detonate only in tracked vehicles, using a blend of acoustic, seismic, radar, and infrared technologies to autonomously detect, track, and engage armoured targets without approaching the vehicle directly: indeed, a shift from traditional contact mines to sensor-fuzed, top-attack smart munitions (Army Recognition, 2023). The 1B75 Penicillin artillery reconnaissance system is similarly designed to monitor enemy anti-aircraft defences and any missile firing positions by combining optical, thermal, seismic, and acoustic sensors to passively detect enemy fire and compute firing positions with high precision without using radar, without leaving a trace, without being detected (Defense Mirror, 2023). Both are part of a new generation of acoustic weapons and have reportedly been used in the Russo-Ukrainian war.

In this evolving landscape of signal and information saturation, silence, secrecy and sensory interception acquire added strategic surplus value, and the unsound takes on its different connotations.

Signal-Based Echoes

Acoustic space is not occupied by sound; it does not contain sound. However, it is constituted by the ontology of sound, by the constantly pulsating relations between oscillating flows. It resembles a fantasy image of a sea of air pressure, but only as an outline; a fleeting geometry shaped by sonic events. And yet, it may include sound. It encompasses anything that operates within the conditions of development and potentiality of acoustic waves. Signal-based media act as transverse additions within that space, modulating waveforms, coding optical images, ideas and sensorial effects – transmitting, archiving, recoding and demodulating sonic events according to the protocols of the information economy within networks of control, access, and value.

In Learning from YouTube, Sean Dockray (2018) explains how Google builds a sound bank, the Audio Set, using millions of samples taken from YouTube videos to train machine-listening algorithms aimed at creating sound-based systems for prediction and control. His goal is to show how user-uploaded videos are repurposed – usually without awareness – into datasets that feed surveillance and machine-learning systems, raising questions of data rights, control, and commodification. A Louroe Electronics product capable of analysing and detecting sounds, the Audio Analytics is already in use, providing security services. At the same time, the American software company Palantir Technologies collaborates with the New Orleans Police Department on predictive policing. A woman’s scream, the laughter of children playing in a square, the sound of glass breaking in an automobile dealership, a gunshot in public space – all of these are samples of sounds that are reinterpreted within their dedicated categories in archives that feed back into sensors placed in public areas for the purpose of surveillance and predictive policing. ‘The preemptive logic of the broken-windows theory […] is reinforced by these algorithms’ (ibid., p. 103), aiming to indicate an event before it turns into a crime. Signal-based media are sonic time machines, Ernst (2016) argues. In this case, they fulfil their operative logic by encoding meaningful – i.e., indexed – soundscapes, snippets of events, into big data that feed back into the experience of the social environment through sensors and detectors, thereby enabling its real-time control. For Massumi, preemptive logic characterizes ontopower. And it does so when the sense of threat becomes ubiquitous and generic. But this is not a subjective affect. It is derivative of systems operating within cultural and environmental conditions, such as those described above, which ‘internaliz[e] them as the motor of their own ongoing patterning’ (Massumi, 2015, p. 38).

Different incidents are anchored in the same signal-based infrastructures. In a report titled The Future of Deception in War: Lessons from Ukraine, Ryan and Singer (2025) explain how the oversaturation of informational signals poses different challenges for battlefield strategy. These include strategies that involve leveraging silence over misleading presence, reconstructing the right narratives from disparate data sets, and filtering information according to points of tactical advantage. Decoys of anti-missile systems and tanks now need to be accompanied by fake heart pulse signals in order to pass as real. Overloading the electromagnetic environment with noise becomes a way to obscure meaningful data – such as drone signatures. Similarly, GPS ‘spoofing’ is used to misdirect drones by feeding them incorrect geolocation data. The writers observe that the use of artificial intelligence for analysing real-time data from commercial sensing and networks – terrestrial, aerial, and maritime sensors employed by non-military commercial entities – has significantly enhanced battlespace awareness. As each piece of hardware leaves its own signature, being able to detect and exploit adversary signatures becomes essential. Such as, for example, targeting a senior commander by the concentration of communications networks around them, by their distinctive decision-making style, or by communicational patterns identified in tactical operation. ‘While each individual person can be seen, heard, smelled, etc., some […] have more prominent signatures’, they explain (ibid., p. 31).

Indeed, there is no actual sound here. Everything has been converted and encoded into electromagnetic signals: movements, navigation, conversations, noises, social media posts, silence, orders; even heart pulses. Strategic advantage is gained through intelligent interpretation of the environment, now enhanced by electromagnetic imaging. Preemptive action requires no actual event. It mimics the event by mapping the conditions of its assemblage; it is radiographed in acoustic space, anticipating the ratio of their reverberations. In that sense, it is ontogenetic, as it colonizes acoustic space for the resonant event that comes next. As Massumi (2015, p. 50) claims, ‘preemptive power infra-colonizes the environment of life toward the emergence of a macroprocess as ubiquitous, as indefinite in reach, and as tendentially monopolistic as preemptive power is itself’.

Derivative Signal Ecologies for a Dangerous Ontopolitics of Sound

An examination of the (military and non-military) research into the unsound shows us that it is not only sound that becomes dangerous and threatening, but also listening. The unsound is inextricably tied to audibility from the onset. Listening is weaponized to detect the movement and direction of ‘threatening’ objects that would otherwise be unheard, soundless, and non-existent in the field of perception. Patricia Clough sensibly says that ‘sonic warfare is more about imperceptible sounding below or above human hearing but which nonetheless affects the human, pushing it to the edge of nonhuman-ness […]. But it is now of a sophistication too, of a technoscience that has taken up the transsensorial or the affective sensorium in order to find ways to modulate conscious perception through the indiscriminate rhythms of vibration’ (2013, p. 68). Indeed, ‘acoustic detectors’, ‘sonic surveillance’ mechanisms, directional speakers, acoustic weapons, microwave systems, and vortex cannons, show us that the properties of audibility are mechanically augmented in both acoustic range (Hz) and sensitivity (dB); the spectrum of audibility is artificially extended by external devices. And the ontology of the acoustic organ – the ear – let alone sound waves themselves, is prosthetically enhanced by recording media, electronic networks, signal-based storage devices, as acoustic sensors and radars create data banks and maps of the paths of objects’ movements, now on a planetary scale.

Ernst believes that the concept of acoustic space marks an epistemic intersection from sound to the sonic: that is, from the range of frequencies that evoke acoustic sensation within the cultural auditory experience, to a range of mechanical waves that transcend the horizon of audibility. While retaining the characteristics of sound behaviour, such waves are converted into electromagnetic signals and, through amplification, transmission and processing devices, (de)modulated into visual patterns or derived articulations of sound. ‘What looks like a visual event in fact turns out to be a function of time-based sounding’ (Ernst, 2016, p. 30). Streams of frequency impulses weave networks of data in the electromagnetic field that ‘descend’ into circuits between transmitters, receivers, and computer decoders that demodulate the signal into a derived order of sensed frequencies – into new fields of stimuli for the consciousness. From this perspective, the acoustic space introduced by McLuhan in the 1950s as the field of operation of electronic devices, discussed as a ‘return’ to pre-literate culture (McLuhan 2005, p. 71), did not exactly involve an idealism of an immanent, primordial, and unmediated (even by discourse) dwelling in the world, characterized by affective resonance and reflexive attention. It was (even implicitly) about the revelation of a field of electromagnetic diagrams that allow us to observe derivative circuits radiographing the unsound objects of the world in real time for the purposes of surveillance, intelligence gathering, and military operations – the realm of thanatosonics (see Daughtry, 2014).

Experiments such as those of Tandy and Lawrence, and Gavreau’s research team do not gain value in the discussion of sonic weapons as speculative investigations of paranormal or mythical phenomena – anecdotes that indicate the limits of military acoustic applications. The scarcity and concealment of (largely classified) information by the military industry makes such anecdotal investigations interesting, since they all share similar working hypotheses and end goals. They all border on the ontopolitics of the environment, involving the governance of an (indeed speculative) economy of sensory stimuli aimed primarily at affect and perception. The publicity surrounding the military’s interest in acoustic weapons in the 1990s seems to have been sufficient to renew academic interest in what sound is and what sound can do, bringing such ‘paradoxical’ associations to light. It has highlighted the involvement of military industry in research that tends to blur the boundaries between sound and unsound objects, sound and information, sound and the senses.

The ontopolitics of sound blurs the previously distinct boundaries between environment, sensory perception, technoscience, and media. Here, sound no longer simply resonates within the world. It co-produces the very conditions of environmental life – the very milieu of ontopolitics, for Massumi (2015). Epistemologically, sound becomes infrastructural. It modulates affective atmospheres, contours patterns of movement, and scripts the thresholds between signal and noise, threat and presence. In applied military research on acoustics, sound is articulated for a quasi-lethal reception within a politico-industrial complex that frames it as an ingenious – if not opaque and mysterious – strike: sonic force without projectile, impact without trace. It is deployed as a sensory incursion, targeting the body as if it were nothing more than a resonant cavity, a drum skin tuned for distress, disorientation, and shock. But sound is also refigured as a derivative presence, a spectral remainder of virtual presences: a flicker in radiographic imaging, a modulation in flows and frequencies, a ghost signal in a field of algorithmic surveillance responding to fictional archives and speculative environments.

Listening speaks, Bonnet proclaims. It grasps stimuli as sound. It renders acoustic waves meaningful. Listening speaks, while the world expects to be heard. But dangerous, precarious, listening constitutes a threatening reception, a malevolent speech; it is the weaponization of sensory responses, the folding of perception into tactical systems. To listen, thus, is to enter a political regime of vulnerability and exposure, where the act of perception becomes inseparable from mechanisms of targeting, recording, and prediction. In the ontopolitics of the 21st century, the body is no longer only a site of experience, but a test subject in simulations of threat; its testimony is converted into data streams, its resonance is measured against probable futures. What seems theoretically urgent, then, is not to read acoustic space through the poetics of soundscape or the metaphor of immersion in the world alone, but to also recognize it as a field of operational epistemology, where sound as an ontological modality indicates intelligence, superintendence, and the modulation of life itself. In this register, acoustic space becomes a medium of control, a diagram of preemption, and a sensorium of power – one that listens back.