Introduction: The Sounds of Melissa

From July 2023 to January 2024, a research team of the EU-funded project ERC MUTE (National Hellenic Research Foundation)1 organized a series of workshops on sound and migration in collaboration with Melissa: Network of Migrant Women.2Melissa, the Greek word for ‘bee’, is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) founded in 2014 by migrant and Greek women activists, who played a leading role in grass roots organizing and the struggles for citizenship rights in the 2000s in Greece (see Zavos, 2010 and 2014). Melissa has become a ‘safe hub’ for migrant women of different ages, races, ethnicities, nationalities, and social classes. Melissa’s community centre is filled with the sounds of the activities and exchanges that take place there, including free lunches, sweets, coffee, and tea, Greek and English language classes, individualized mental health support, a day care centre for children, and occasional workshops offered by volunteers that include a choir, yoga classes, IT, cartoon- and video-making.

Located at Victoria square in central Athens, Melissa’s community centre is housed in a three-storey interwar building with high ceilings, cracking wooden floors, and wooden windows. When inside the community centre, one notices long periods of quietness, then several voices speaking simultaneously in different languages and accents. Sounds from the outside also permeate the building: it is impossible to evade the noises of road works or heavy traffic when being on the inside. Especially in the hot summer days, there is no other option but to leave the windows open. At the same time, sounds circulate from the inside outward: passers-by cannot avoid hearing the sounds coming from the community centre. Melissa strives to form a safe space for migrant women, secluded from but also interconnected with the surrounding area. Melissa is protected but also porous: both sonically exposed to outside noises, but also constantly spreading to the surrounding public space with the sounds of women speaking, singing, and performing in different languages.

The sounds of Melissa are spread in the broader region of Victoria Square, an area covered by modern high-rise blocks of flats, narrow pavements, and some large roads with densely packed sideways and heavy traffic. Once outside, sound does not circulate freely and everywhere. It gets trapped in narrow roads with high-rise buildings. During the 1970s and 1980s, the area was abandoned by many of its Greek inhabitants, who moved to the suburbs of the city to escape air and noise pollution, overcrowding, overheating in the summer, and lack of open and green spaces. In the 1990s, however, Victoria was radically transformed into a ‘migration hub’ (Tsavdaroglou, 2018; Martini, 2024). Ever since it became a space of migrant settlement but also of a transit spot renowned across translational migrant networks, inhabited ephemerally by those who pass from there on their way to other safer destinations.

Victoria square is the only open, public green space in this region, where sound can travel more freely. However, sounds are segregated along ethnic, racial and gendered lines. The centre of the square is surrounded by plants that block some of the noise of road traffic. After the summer of 2015, the municipality of Athens planted trees and bushes and placed railings around them to prevent migrants from squatting there (Makrygianni, 2024). The plants separate acoustically the centre of the square from the mostly Greek dominated coffee shops, restaurants, and kiosks that are located behind them. In these commercial spaces of the square, one can mostly hear voices speaking in Greek, often with an accent. On the contrary, in the centre of the square, protected by the sound insulation of the plants, it is more common to hear migrant male voices speaking different languages. These are audible alongside the sounds of commuters, who come and go in front of the underground railway station. The voices and sounds of migrant women are rarely audible on the square. One artistic project tried to appropriate this male dominated public space by an in-situ broadcasting of the collected sound material from migrant women talking in English, Greek, and Farsi (Diakrousi, 2017).

During the pandemic, Refugee Support Aegean (2020) posted a video, where we can still hear the voices of Afghani children, women and men who squatted the square blurring with the road traffic. The occupation of the square in 2020 was one of many. It was the result of the Greek government’s executive decision to exclude asylum seekers from access to housing programmes for refugees once they received asylum. These occupations turned Victoria into a ‘contested space’, where precarious Greeks antagonized migrants who settled there or were in transit (Kandylis and Kavoulakos, 2011). There were periods in the 2000s when the space of Victoria Square was dominated by racist conflict, police violence, but also solidarity, and anti-racism. These intense sounds were backed, on the one hand, by sensationalist media reporting, portraying it as an ‘insecure space’ and, on the other, by idealized reports by international academics and artists that romanticized its multicultural vibe presenting it as a ‘city of refuge’ (Turam, 2021; Lowe, 2017). Activist solidarity in support of migrants not only did they clash with ultra right-wing groups, but also with NGOs and the Municipality of Athens, which promoted humanitarian approaches.

The Politics of Translation

During a workshop session, I asked a group of migrant women to read and sign consent forms; long texts, which require ticking ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to complicated questions related to the ethics of research. The forms were translated into different languages that participants could understand, including Arabic, French, English, Urdu, and Ukrainian. I explained their content in Greek and added that their aim was to protect their rights, ensuring that researchers, like me, would not use their contributions and exchanges without their consent. The forms provoked debates in different languages that I could not understand. Questions were being asked, and responses were improvised by the translators. Listening to the recordings again, I heard an intense sound, a buzzing of words being explained, transformed and renegotiated in different accents, tonalities, and languages. This paper addresses and reflects upon this buzzing from the perspective of a politics of translation.

Translation is often understood as the communication of a message to readers or audiences, who cannot understand the language in which it was written or uttered. However, translation is not only about what but also about how a text is written or uttered. Translating is a complex act that has political implications. A good translation doesn’t have to reproduce faithfully the original, but to become an ‘echo’ or a ‘reverberation’ of the original. Instead of copying the original, it makes it possible to come to terms with the ‘vagueness of language’ and share its indeterminacy (Benjamin, 1997, p. 159). Rather than a means of communication, translation becomes a paradigm of encountering the Other (Ricoeur, 1997). When translation absorbs violently what is being written or uttered in a foreign language, it may be transformed into an act of hostility towards the Other. On the contrary, when translation is freed from the obsession with fidelity and meaning, when translation opens up to otherness, it becomes a ‘paradigm of hospitality’, a political ethos that encourages exchange and transformations of both the host and the foreigner (ibid.; Kearney and Fitzpatrick, 2021).

The politics of translation have influenced profoundly contemporary thought on migration, gender, and transnational feminism. In many analyses, migration and translation have become interconnected concepts that instruct the ways in which we understand community and otherness, identity, and alterity (Papastergiadis, 2000). Translation by migrant and diasporic subjects has been identified as a performative act that makes possible cultural hybridity and in-betweenness, putting into question the homogeneity of national cultures, but also the authority of those who utter and write it (Bhabha, 1994, p. 228). In everyday life, the work of cultural mediation that translators perform in activist and community contexts differs from the work that official interpreters undertake in the context of institutional procedures (applications for asylum, residence permits or citizenship), although the limits between these two practices may often be porous. Translation works in conflicting ways. It may become a violent practice that impacts negatively on migrants’ socioeconomic and political rights, but it also has the potential to enhance the agency of migrant subjects and their audibility in public spaces (Polezzi, 2012).

The politics of translation have inspired many important texts and practices of translocal, post- and de-colonial anti-racist feminisms (Alvarez et al., 2014; Spivak, 1993). While translation provides a conceptual framework for the inclusion of diverse experiences and identities, it is also often used, especially in postcolonial contexts as a tool to impose a misleading homogeneity in women’s experiences. As English is imposed globally as the language par excellence of gender and feminism, all texts, all actions, all utterances appear to be part of the same continuum, of the same seemingly undivided sisterhood (Spivak, 1993). Nevertheless, translating the Anglo-Saxon feminist concepts in other languages may have no relevance to local experiences. Attempts to translate feminist concepts in different languages are often met with resistances and accusations of cultural imperialism. The difficulty in translating ‘gender’ into other languages is indicative of how linguistic hegemony may impede transnational, translocal, and postcolonial understandings of gender (Butler, 2019). While translation has been an important word in the vocabulary of migration and gender, it has not been widely explored and analysed from the perspective of sound and audibility. The article highlights how a politics of translation enables forms of listening and witnessing that bring to the forefront migrant sonic agencies. It also discusses how heterolingual translation becomes an everyday practice that makes possible resistances to gendered and racialized hierarchies and inequalities. Finally, it considers how making heard and listening to the buzzing of translation enhances the sonic agency of migrant women.

Melissa and the NGOization of Migration

Following the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ of 2007, European Union (EU) funding for humanitarian projects for refugee protection increased, and established international and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) began to operate more widely and systematically in Greece (see Rozakou, 2012). The NGOization of migration led to ongoing tensions, conflicts, and oppositions between the professional humanitarian ethics that identify migrants as the problem and the solidarity ethics of ani-racist social movements that identify borders as the problem (Lafazani, 2018). In contrast to the overwhelming financial and political support that the Greek state and the EU gave to NGOs, a regime of criminalization and suppression of informal solidarity practices was instituted in the Mediterranean, targeting especially rescue operations at sea and housing occupations organized by migrants and solidarity activists (Mezzadra, 2020). In an environment of widespread unemployment, however, many migrants and solidarity activists found precarious jobs in these NGOs, and were consequently forced to (re)negotiate their political principles, reconciling their activist identities and practices with gatekeeping and participation in humanitarian migration management (Pendakis, 2021).

Although Melissa is not a space free of intercultural and intergenerational power dynamics and hierarchies, it differs from most NGOs in Athens. It is not gravitating towards the prevailing humanitarianism of NGOization, but is founded on the principle of migrant women’s solidarity. Contrary to the world of humanitarianism which ‘is populated by victims’ and is constantly focused on resolving ‘emergency’ crises (Mezzadra, 2020, p. 427), Melissa insists on the long-term needs and demands of migrant women and their powerful potential to contribute to and transform Greek society. Its approach is based on providing slow responses, care, and support to enable migrant women to utilize ‘their scarce resources’, to ‘make something out of almost nothing’ (Melissa, 2024). Many of Melissa’s participants experience or have experienced in the past prolonged and painful periods of vulnerability and victimhood because of wars, conflicts, detention, police and gender-based violence, precarity and uncertainty, only to find themselves being treated in paternalistic ways by states and private agencies that seemingly protect them. Melissa refuses to reproduce these patterns of victimhood and paternalism and to engage with charity-based politics. It strives instead to establish gradual trust and relations that last, treating migrant women as active participants in a network. It challenges activities that reproduce unequal relationships between, on the one hand, NGOs as generous and charitable providers and, on the other, migrant women as passive aid recipients. Melissa constitutes a space where most employees are migrant women, who also have experienced vulnerability, precarity, and violent border crossings. Although performed in an NGO framework, the politics of Melissa are aimed at a restitution of a sense of agency and humanity that migrant women have often been denied in migration management processes carried out by state agencies and humanitarian NGOs.

Beehive Methodologies

Most music workshops adopt didactic and healing approaches based on teaching migrants how to perform, write, listen, edit, or collect sounds and music. Improvisation and free selection are frequently chosen as tools to help researchers, NGO staff, volunteers and even detention officers overcome asymmetrical power relations and tensions with migrants (Hughes, 2016). Several analysts perceive them as ‘practices of hospitality’ and sharing, enabling otherwise isolated and traumatized migrants to connect with local communities and transcend linguistic and cultural barriers (De Martini Ugolotti, 2022 and 2023). Some authors argue that through these intercultural sonic practices, ‘accidental communities’ may produce positive impacts on dispossessed migrant lives (Weston and Carolin, 2016; Weston and Lenette, 2016). Some scholars argue that music learning and playing is less about learning music per se and more about working in common around feelings of discontent, disappointment, and experiences of displacement and alienation (De Martini Ugolotti, 2022 and 2023). Music workshops are, thus, also used as practices that produce ‘healing spaces’ (DeNora, 2013), which give back to the displaced a sense of ‘humanity’ that is valuable especially when having to wait indefinitely in a state of uncertainty and precariousness in detention or in camps (Hughes, 2016; Underhill, 2011).

Although such workshops may have positive impacts on some migrants, they tend to rely on and celebrate an ethics of humanitarianism that silences migrant agency and the complexities of migrant everyday lives. While they reproduce abstract notions of music and dance as universal languages that transcend cultural and linguistic boundaries, they lack consideration for the materiality of sound (Shao, 2023). Their didactic and healing approach relies on – often unspoken – unequal relations between migrants and the professional musicians, sound artists, researchers, and NGO workers. The skills and knowledges of the latter are valorized and considered as worth teaching, while migrant participants’ skills and knowledges are often devalued, marginalized, or even silenced. These asymmetries are exasperated by the precarious situation in which many of the participants find themselves during workshops. Migrant participants are expected to express gratitude, relief, and joy because they are given an opportunity to become part of a community, be themselves, or heal their traumas through music, but they are not expected (or even allowed) to express anger, frustration, despair, anxiety, make fun of or criticize borders, policing, violence, detention, and especially humanitarian migration management through music and sounds. Within a context of protracted anxiety and uncertainty caused by border and humanitarian regimes, workshop organizers may become unable to cope with the more traumatic experiences of participants, their continuous precarity, let alone contribute to their healing (Lenette and Procopis, 2016).

In our project with Melissa, we sought instead to identify alternative workshop practices that rely on critical and collaborative methodologies, and enable sonic perspectives that unsettle and rupture linear storytelling, bringing to the forefront how messy life is when crossing borders (Western, 2020). Our workshops were mostly inspired by feminist methods and techniques, especially digital storytelling, that prioritize sharing, listening, and co-editing personal stories with the active participation of migrant women (Vacchelli and Peyrefitte, 2018; Dennis et al., 2020). These methods allow migrant participants to tell their stories in their own terms, using their own languages, their own sounds and silences, their own rhythms and movements. In our workshops, however, we focused on sound. Migrant women were invited to experiment, discuss and contemplate on how they listen and how their voices and bodies can be heard by others. We, as researchers, would listen to migrant testimonies together with them, and explore techniques to represent them in ways that are respectful and recognise their agency. Our common listening and making heard did not only include witnessing sounds of pain, violence, displacement and trauma, but also sounds of humour, criticism, frustration, irony, anger and disrespect for border and humanitarian control. Although we were supported and advised by a specialized psychologist, it was clear that taking part in such a project without appropriate training could be risky, unwittingly contributing to the re-traumatization of participants and the wounding of researchers. In this context, we decided that it was crucial to adopt a self-reflexive stance, making time for relations between participants and researchers to unfold without seeking to constantly teach them knowledges and skills, extract data from them, and especially ‘heal’ them (De Martini Ugolotti, 2022).

Most collaborations that NGOs develop with researchers produce humanitarian discourses that often marginalize or exploit the narratives of migrants for their own funding and policy goals (Saltsman and Majidi, 2021). This is a vital process through which refugees become visible in specific victimized ways, but silenced more broadly (Malkki, 1996). Migrants experience this silencing as a violent process, whereby their disclosures and life-stories become filtered by NGOs and researchers to meet broader humanitarian causes and academic objectives (Rajaram, 2022). This is the case especially with migrant women’s voices that do not conform with the stereotypes of humanitarian victimhood, or go too far towards the direction of criticizing and expressing rage against borders, policing and gender inequalities become even more inaudible (Kihato, 2007). By emphasizing migrant women’s agency and the valorization of their resources, Melissa’s approach challenges the interconnected logics of victimization and humanitarian paternalism. By adopting Mellisa’s beehive methodology, we engaged in practices of listening in common with migrant women that made it possible for us to trace sounds that are often unnoticed in humanitarian discourses, especially the buzzing of heterolingual translation, which has inspired this article.

As Ruha Benjamin (2024) argues, bees are ancient symbols of ‘radical interdependence’ that promote collaboration and pollination, multiplying the positive impacts of their work on their community but also on their wider environment. However, bees are also ‘visionaries’: due to their short life spans, they never actually experience the results of their hard work but work for many others who will come next. The beehive methodology that Melissa promotes is about imaginings of alternative possibilities and common futures for migrant women. It allowed us as researchers to problematize the audibility of gender, how it becomes heard and echoed in public spaces or within migrant communities. While we were preparing the workshops, we met with some of Melissa’s coordinators and discussed our idea to devote one session for a sound walk in the area. We were told that it would be better to avoid Victoria Square. We were advised to direct the walk towards the park in front of the Archaeological Museum because most of them feel much safer amongst foreign tourists. In fact, some workshop participants confirmed later that they only pass through Victoria square to avoid accidental meetings with strangers, but also with male members of their own migrant communities. For most migrant women, Victoria square is neither a ‘safe space’ that they feel part of, nor a ‘space of refuge’.

Feminist research methodologies proved to be appropriate for a space like Melissa as they are influenced by grassroots activisms that politicize embodied narrating, writing, and listening of experiences of gender inequality, violence, and resistance to produce common political positionings and discourses (Haug, 1987). Following Melissa’s approach, we tried to listen in common to the rich sonic resources that migrant women carry, including their voices, musical knowledges, and sounds that they made, remembered, and recorded. We also tried to listen attentively to their sonic memories of the past without expecting specific genres, tropes, or feelings to prevail. While we organized the discussions, asked the questions, recorded, edited the material, interpreted and analysed findings, we were careful to avoid extracting the rich resources that participants shared with us for our own research purposes and ambitions. The experiences of migrant women are easily and unproblematically ‘copy pasted’ into academic analyses and NGO reporting to suit the needs of academic, NGO and artistic researchers, although they remain silenced and undervalued per se in broader public debates about migration (Rajaram, 2002; Malkki, 1996). Our workshops at Melissa were not about ‘discovering’ and ‘using’ migrant women to create written and audio material for ERC MUTE, but mostly about listening together and making sounds and music that are absent from Greek public spaces more audible.

The first technique that we used was to listen carefully, attentively and collectively (together) with the participants. We tried to question the gendered binary between sound making and music playing as superior, masculine, active practices and listening as a subordinate, passive and feminine practice (Cusick, 1994; Oliveros, 1994). Our aim was to make listening part of a participatory process, in which sharing was the primary aim. In some cases, though, when participants were reluctant to share their personal stories in a group setting or when sensitive issues, like traumatic border crossings or gender-based violence, were discussed, we conducted biographical interviews with individual participants. Listening was not only focused on the content of the narratives or the genre of music that was played or performed, as in more traditional musicological analyses, but also on embodied practices. Through this emphasis on embodiment, we tried to make our listening less gender neutral (Cusick, 1994) but also more ‘androgenous’, at the same time aiming for passive and active approaches (Oliveros, 1994). We drew inspiration from feminist perspectives that analyse how music genres and performances are regulated according to gender norms in local communities, but also from how women and LGBTQs transgress heteronormative boundaries through music listening, making, and playing (Koskoff, 2014). This approach provided a basis for a listening of femininities, and occasionally also of other gendered subjectivities, that do not easily conform with these binaries exposing positions of vulnerability and resistance in between.

The second technique that we used was to record sounds, music, discussions, and interviews and produce podcasts that were co-edited with participants, whenever possible. This technique resonates with ethnomusicological ‘dialogic editing’, a process of ‘translation’ of research and analysis of music and sound into the local linguistic and cultural norms and modes of knowledge and cultural production that prevail in the communities that are being researched (Feld, 1987). Through this process, we soon realized that editing helped us shift our attention towards the ‘mundane’ everyday acts that otherwise remained unnoticed. By recording and editing podcasts in common with participants, we hoped to ‘give something back’ to Melissa, but also to make more audible sounds, which are routinely silenced and marginalized in Greek public spaces. The co-editing with migrant women, whenever it was possible, became an alternative strategy to the usual copy and paste that is prevalent in humanitarian discourses, opening ways to explore undervalued sounds and music that researchers and NGO staff usually discard as irrelevant. During the workshops, we emphasized processes of participatory making audible, where the subjects who were heard in a podcast were actively encouraged to have a say in its aesthetic and content. Making audible became an area of contestation and problematization, which became more complex and multifaceted as participants were influenced by gendered, aestheticized, and racialized norms and stereotypes that prevail in a globalized world. Our listening became an exercise of traveling across borders, but also of witnessing how global norms become appropriated and transgressed in local musical practices (Lemos, 2011). Through listening in common and making audible, we tried to disengage diverse music and sound practices from notions of ‘authenticity, ethnic specificity, and local/world dichotomies, and divisions’ (Schiller and Meinhof, 2012, p. 34). The workshops became instances where we could listen and produce sounds and music from different localities and cultural starting points, manifesting transnational, local, and national influences and interconnections, but also cross cutting themes, translocal commonalities and appropriations of musical genres and techniques that broadened our ways of understanding migrant women’s trajectories.

The Buzzing of Translation

The main participants who attended the workshops regularly came from Algeria, Cameroon, Congo-Kinshasa, Egypt, Morocco, Lebanon, and Ukraine. One woman from China, one from Iran, and several women from Afghanistan attended the workshops sporadically. Also present were a Greek Lebanese and a French translator as well as the three of us – all Greek researchers. Amongst us there were Muslim, Christian, and agnostic women, some living with their families, others with friends or as singles. Some were asylum seekers, some were refugees, others were immigrants with or without papers, most of them living in very precarious conditions, and only a few of them in more settled and stable situations. What the participants had in common, however, was the fact that they all lived translocal lives constituted by transborder and transcultural experiences; they had developed translocal subjectivities formed through their everyday interactions and exchanges with other women from the Global South both outside and within the network of Melissa (De Lima Costa, 2014).

Workshop sessions began with an open question to allow women of different experiences, cultures, languages, and trajectories to participate in common discussions and listening. When asked about the sounds that remind them of home, participants remembered various sounds of their childhood and family life that are not audible in Athens. They narrated stories about the voices of relatives and friends, played music and sounds of nature, animals – including silences – seeking to find connections with a past that they had left behind and that they might never revisit. A Ukrainian woman remembered the nostalgic sounds of frogs in her country home, and of sleeping in the arms of her father as a child. A young girl from Afghanistan remembered the soothing sounds of birds singing in Kabul, where people train them to fly outside their cages and return. A woman from Ukraine remembered an eerie silence in her home before fleeing to come to Greece. She lived next to an airport and when the war started all flights stopped.

Once a story of a song or a sound memory was shared and discussed, we tried to find it online in open-source databases and listen to it. We listened together to the sounds of the sea waves. For migrant women from Ukraine, the sounds of the sea were comforting, pleasant, and relaxing, reminding them of the holidays they took when they visited Greece as tourists before the war. For a woman from Cameroon who crossed the Aegean from Turkey at night inside a boat that was almost sunk by the Greek coastguard, the sound of sea waves was violent and threatening. Listening together to these sounds allowed us to rethink different migrant trajectories, explore their divergences and convergences and discuss how they make us feel. We discussed how different female bodies are affected and moved when hearing the same sounds that bring back memories of a past that haunts or comforts them. During a sound disco, participants were asked to DJ for the group. A Moroccan woman played and sang loudly Arabic songs that she used to ‘sing quietly’ as a teenager, because her family did not think that she could sing well and always warned her not to sing, for singing was perceived as a sign of arrogance and vanity. Another Arab woman from Egypt also remembered how she used to listen to Arabic music on her walkman with her sister. She played for us a series of Arabic songs that she selected online. Women from Morocco, Algeria, and Lebanon sang along and danced, while a Chinese woman and other women from Ukraine clapped.

These sessions did not only revolve around memories. When asked about sounds they dislike, a migrant woman from Iran commented in a humorous and ironic voice that the sound she hates the most is the sound of the word ‘NO’ in Greek [ochi]. She explained that each time she carries out bureaucratic chores, this hateful sound is uttered by the NGO and state administrative staff. She felt powerless with the repeated utterances of ochi: ‘Ochi, we don’t speak English’. ‘Ochi, we don’t have this information’. ‘Ochi, we cannot help you’. ‘Ochi, your application is not complete’. The sound of ‘NO’ (ochi) manifests from many migrant women a sense of being displaced or even misplaced in Greece, but also the impossibility of integration. The workshops made more audible mundane, every day, messy sounds that are often unnoticed in migrant women’s narratives, commonly reproduced by researchers and NGOs, because they manifest the precarity that many migrant women continue to experience even after they acquire residence permits or humanitarian protection (De Lima Costa, 2014).

In some narratives this sense of displacement/misplacement was also reinforced by sounds that made ongoing conflicts and violence in their home countries very present in their current lives despite the temporal and spatial distance. For instance, Ukrainian women narrated how the sounds of sirens, military aeroplanes, and parades that are common in the centre of Athens during national celebrations bring back traumatic memories of war. They told the group how their bodies react automatically and instinctively to these sounds, provoking a sense of insecurity. We tried to rethink together with them how we perceive these sounds as part of a nationalist ceremony and how differently they might be experienced by bodies traumatized by war. In spite of their feelings of anxiety and loss provoked by the war, most of the Ukrainian women showed us mobile phone apps, which they use for getting real-time updates on the war. We also listened to the low-voiced disclosure of gender-based violence (GBV) that one refugee from Congo Kinshasha made. She told us that she could not relax in Athens from the noises in her head. Every time she heard the voice of her sister on the phone, the violence returned. She sang a healing and soothing religious song and selected music on YouTube from her favourite Evangelical Pastors for us; these were the sole sounds that calmed her down and made her feel safe. As Rubah Salih (2017) argues in her analysis of Palestinian women’s narratives, memories of war, violence, and displacement are embodied and focused on everyday lives and ordinary bodily acts, involving love, births, children, relatives, domestic spaces and care, but also domestic violence though not battles and heroic nationalist struggles.

All the discussions were recorded and then edited in collaboration with the participants. However, in a few cases some participants decided that it was too painful for them to listen to their voices again, or that it was too time-consuming to participate in editing. While we were listening to the first recordings, we started to realize that there were also sounds that we did not know how to edit. For example, there were sounds of babies and children, who cried, laughed, ran, or watched videos on mobile phones, the sounds of an autistic son who did not want to be left without his mother in the day care centre of Melissa. These sounds manifested the care burden, but also the optimism for the new lives that many of these women were now building in Athens.

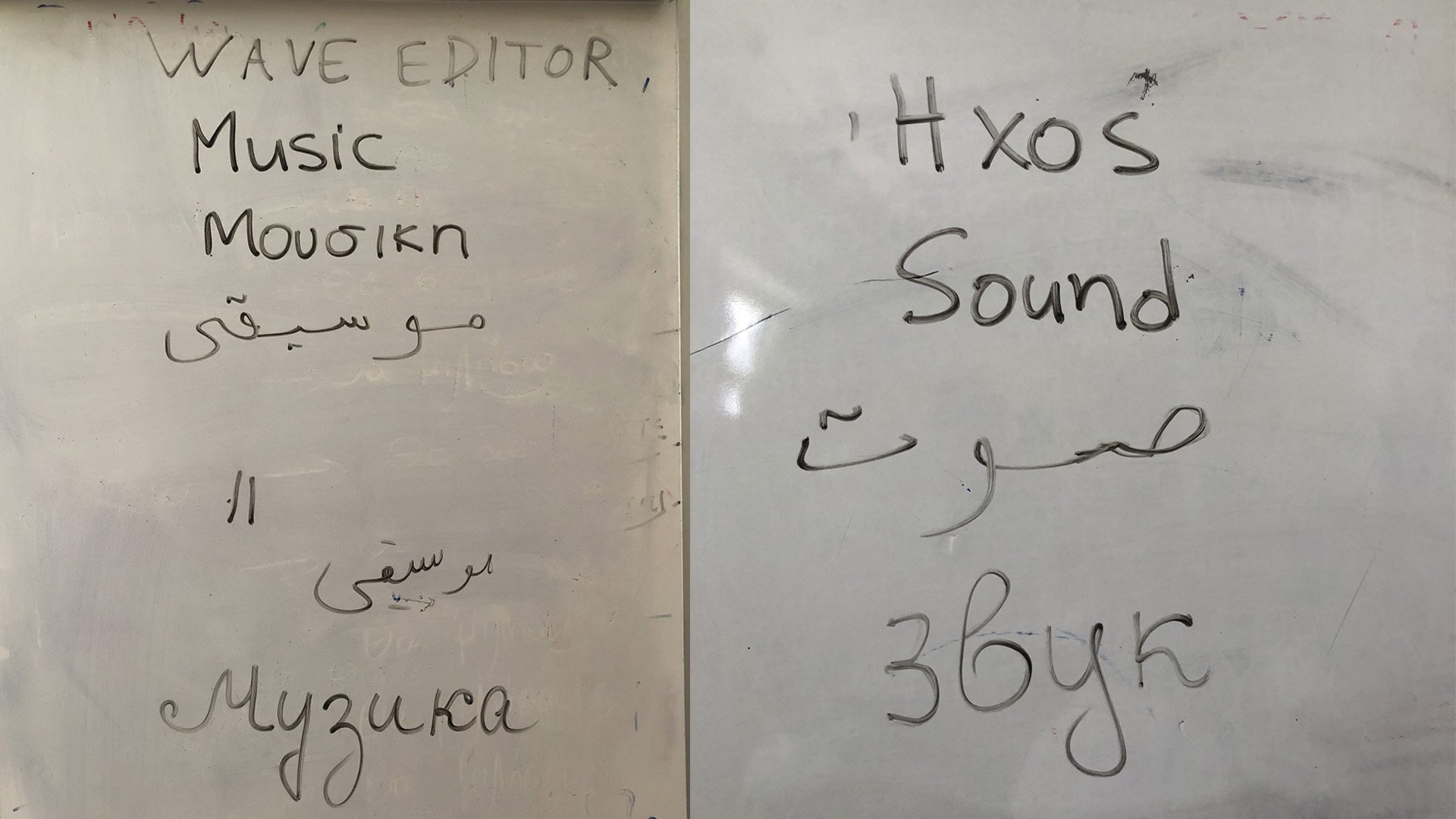

Equally puzzling for our editing practices were the sounds of translation. During the workshops, each enunciation, each story, each demand, each song, each poem was translated into Arabic, English, Farsi, French, Greek, and Ukrainian. Translations are embedded into all of Melissa’s activities. The translators, who act as ‘cultural mediators’, are in most cases migrant women themselves. Their presence in our workshops was valuable. However, it prolonged the recordings making it difficult to cut because the different languages intermingled, creating a complex buzzing that made it impossible for listeners to discern the meaning of what was said even if they could understand some of the languages spoken. A useless noise? We had to address this question first as a problem of time and sonic aesthetics, and then as an issue of the politics of gender and migration.

Nakoi Sakai (1997) identified two modes of translation. First, homolingual address is a regime of enunciation, in which the translator ‘adopts the position representative of a putatively homogeneous language society and relates to the general addressees, who are also representative of an equally homogeneous language community’ (pp. 3–4). This type of translation obscures the fact that in most languages and in most audiences, there is multiplicity, and that the language of the translators is not identical with the diverse languages that those who are part of the same community share. Translation thus may reinforce cultural and socioeconomic boundaries and hierarchies, constituting a unitary national, ethnic, or linguistic ‘we’ (Neilson, 2014). In the heterolingual address, on the contrary, the language of the translator is one of multiplicity and in-betweenness, where enunciations are addressed to ‘an essentially mixed and linguistically heterogeneous audience’ (Sakai, 1997, p. 4). In these conditions translation constitutes a complex community, a ‘we’ that is not unitary. ‘In order to function as a translator, she must listen, read, speak, or write in the multiplicity of languages, so that the representation of translation as a transfer from one language to another is possible only as long as the translator acts as a heterolingual agent and addresses herself from a position of linguistic multiplicity: she necessarily occupies a position in which multiple languages are implicated within one another’ (ibid., p. 9).

In Melissa, translations are not directed from a minor to a hegemonic (European) language, for example from Arabic to French, or from Ukrainian to English, or from Farsi to Greek. Instead, Melissa’s cultural mediators work together with participants to translate in multiple other languages, in the languages of all those who are part of a group. These multiple and multidirectional translations produce a constant sound of diverse voices, languages, and accents. To listen to this buzzing is to listen not only to languages that are incomprehensible but also to the multiple ways in which colonial languages, like French or English, sound differently when uttered in the accents of postcolonial subjects, but also when uttered together with other translations. It is also about allowing mistranslations or free interpretations to become part of the process. As one of the translators explained to us, phrases and words had to be made intelligible not only in different languages, but also in different dialects as migrant women from within the same nation-states or from different nation- states that share the same language may not share the same vocabularies. Moreover, affects, feelings, and gestures of sadness, joy, enthusiasm, longing, nostalgia, pain, fear, disappointment, anger, and frustration were also translated and made intelligible in different cultural contexts through physical gestures that vary from culture to culture.

The sounds of translation are the product of a complex but intricate and detailed practice that unfolds and expands the limits of listening in common. By listening to the buzzing of translation, we witness the unfolding of a different politics that unsettles the hierarchical relations between researchers and participants. This listening imposed on us as researchers a slow pace and a heightened awareness of voices that are not easily intelligible or easy to follow. It imposed on us a discipline of waiting and being patient for participants to better understand and make meaning intelligible in their own terms. It forced us to try harder to remember languages that we were not comfortable using, to understand words that were not familiar, and to question the ease with which we settle in monolingual practices. Our workshops were not conducted in a universal commonly accepted and shared language, but through a series of buzzing sounds of minor and major languages and meanings being utilized, negotiated, transported, and reimagined.

According to Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1993), a feminist politics of translation resists both capitalist multiculturalism and the hegemonic white feminisms that take as their starting point the common universal experience of women. But this shift to a politics of translation is only possible when ‘one works with a language that belongs to many others’ (p. 179), when one can surrender to these others and forget oneself. This point is of crucial importance, especially when we are so used to translating monolingually from the perspective of a hegemonic language and a positionality that assumes that European, white, middle-class experiences of gender inequality are universal. When translation is monolingual, always directed towards the hegemonic language, all feminine subjectivities become identical, all feminisms sound the same as if they emanate from the same universal experience of womanhood. For Spivak, translation is mostly about a ‘reading’, which challenges ‘the good-willing attitude of “she is just like me”’, which ‘is not very helpful’ (ibid., p. 183), especially when we read and write from a hegemonic positionality of the dominant gender, race, class, or even of the dominant acoustic aesthetic. In our case it was also about becoming attentive to sounds as well as silences, which questioned our prevailing understandings of migration and gender.

A politics of translation requires to practice listening attentively without the sounds of homogenizing hegemonic feminisms. Through this practice, researchers can learn how to become more attentive to the sonic agency that migrant women are systematically denied in Greek public spaces and also within their own migrant communities. During the editing phase, we proposed to include these sounds of translation into the final products of the music workshops, the podcasts. The workshop participants mostly disagreed with this proposal. They told us that translation was a source of stress for them; it was not what they would like to hear when listening to a podcast about them. Like the sounds of children, it was a part of their lives and they felt that it shouldn’t be heard outside the space of Melissa. They told us that they would prefer instead to add some ‘soft piano music’, mostly European sounds downloaded from popular platforms, because they felt that it would calm the listeners, and better appeal to Greek and international audiences. The podcasts were a means to send a message, so their sonic aesthetics had to be translated into an easily intelligible sound for European ears. This made us rethink the buzzing of heterolingual translation not in idealized terms, but in terms of listening as labour.

In ‘Border as Method’, Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson (2013) turned to heterolingual translation in their attempt to carry out an ‘urgent task’: to overcome a ‘suspicion of calls for unity’ and ‘to invent new methods of organization, translation, and alliance that can arouse and embolden the workers of the world in all their heterogeneity and multiplicity’ (p. 130). This call is in tune with feminist thinking that seeks for collectivity devoid of uniformity. They argue that we cannot understand the subjectivities of migrants that emerge at the borders as single unitary identities. Borders, they argue, do not only produce relations of exclusion, but also forms of differential inclusion, which in turn makes possible the emergence of multiple subjectivities. These subjectivities differ as the borders migrants have crossed are different at various stages of their trajectories. Some of them face the constant threat of deportation and racism, others have papers but live in precarity, and others are in more secure, more ‘integrated’ positions, but constantly under the threat of violence because of racism. What we have listened to in Melissa is a ‘labour of translation’, not only because it entails sounds of different languages, but also sounds of ‘bodily gestures, affective exchanges, rhythmic expressions, and the sharing of pain, sufferance, and joy’ (ibid., p. 278). The outcome of a politics of translation of this type, then, is the production of a collective subject that resists unity, because ‘it is continuously open’ and even when it closes it must reopen to face the challenge of the untranslatable, the misunderstood, the incommensurable. What is important here is that this collective but not unitary subject does not speak the same language but is able to create a ‘working knowledge’ that arises through ‘working together and living together’ (ibid., p. 276). To put it simply, translation is what makes Melissa operate as a feminist postcolonial and antiracist space, which resists NGOization, relying instead on the production of social relations amongst women of different nationalities, races, social classes, ethnic groups, sexualities, languages, legal statuses, and histories that co-exist and interact. Translation is not only or principally about communication, but about commensurability and living in common.

Conclusion: On the Audibility and Sonic Agency of Migrant Women in Porous Spaces

Through the porous windows of Melissa, the buzzing of translation spreads across the Victoria square area. It defies the segregation of race, ethnicity, gender and class that dominates the nearby square. Although it gets trapped in narrow streets with high rise buildings and is hardly audible when the noise of car traffic rises, it can still be heard by the passers-by who are willing to listen to it attentively through the cracks. Although not loud, it is an intense sound of labour that migrant women perform in their effort to articulate in common forms of sharing and caring across borders. Yet, the buzzing of translation is a sound that disturbs and distributes sound in ways that are unexpected and often unintelligible. It constructs a collective ‘we’ , a sense of belonging and community, out of disparate languages, voices, tonalities, intensities, and accents. Migrant women who are members of this community do not share the same linguistic and sonic codes, the same origin, the same culture, or religion. They become part of Melissa’s community because they strive to translate in many different languages, in many different tones, cultures, and religions. What is produced through this process are ‘mundane’ and ‘messy’ sounds of migrant women’s everyday lives; a sound that goes beyond the uniformity and homogeneity of national, as well as of migrant and diasporic communities. Even if the volume of this buzzing is too low to become audible and even if it is not performed in public, it manages to destabilize the national homogeneity at least for those willing to listen.

The buzzing of translation manifests the agency of the migrant women of Melissa. Brandon LaBelle (2021) developed an analysis of the concept of ‘sonic agency’ that is focused on practices of resistance that produce multiple voices to be heard and echoed, disturbing and shifting power relations that rely on centralized political structures and unitary communities. According to LaBelle, sonic agency can take different forms. On the one hand, it can materialize in collective practices of making noise and being loud, or refusing to be audible and being silenced. On the other hand, however, sonic agency is also about acts of listening and of paying attention that challenge established political norms. While listening can be an invasive and violent act, it may also become a political practice that invites collaboration, care, and support. From this perspective, attentive listening becomes ‘a critical and creative position, a stance one also takes in order to engage in the collaborative work of living’ (ibid., p. 4).

Most discussions of sonic agency focus on the ways in which homogeneous public spaces are disrupted by migrant interventions. In the case of Athens, Kareem AlKabbani and Tom Western (2021) wrote about the transformation of public spaces by migrant communities that reverberate political demands from Damascus through music and sound. By becoming audible in public, through music and dance, they rupture the ethnic and racial homogeneity of Greek soundscapes and make possible the development of common political struggles across borders. Through these practices, Athens becomes an anti-colonial city that operates through circular movements of solidarity and support amongst citizens and strangers against the linear logic of colonial time and space (Western, 2023). Music and dance performances, silent marches, shouting for migrant rights, or making audible anti-racist solidarity in public are acts of active citizenship enacting rights where they do not exist. In a short book, Judith Butler and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (2007) explored a feminist politics that questions the homogeneity of the nation state through translation. At one point in their conversation, Butler gave the example of Mexican migrants without papers demonstrating in California against the US border regime by singing the American national anthem in Spanish. She argued that singing this ‘untranslatable’ sound was an enactment of rights where they did not exist, in a public space in a different language that destabilizes the limits of audibility, the national borders, and the boundaries between legality and illegality. The singing in public produced a ‘performative contradiction’ (ibid., p. 64) that enabled a plural mode of belonging and being that intervenes and ruptures established borders and rights.

Melissa’s buzzing of translation is not as audible in public spaces as protest songs and dances are. It is produced in a space that is semi-private and protected, but leaks and spreads in public because of Melissa’s porousness. This reminds us that the public-private divide is gendered. In the past, women were formally denied full citizenship and the right to participate in formal politics but resisted their exclusion by creating spaces of commonality and care in private rather than public spaces (Siim and Stoltz, 2024). Similarly post-colonial migrant subjects who are denied citizenship rights and face racist exclusion, find ways to become political through everyday acts of resistance that cut across the divide between public and private. Many gendered acts of citizenship continue to be audible only if we listen attentively and become aware of global gender inequalities. The buzzing of translation produced in Melissa reverberates these genealogies of gendered and postcolonial citizenship, but does so only for those who are willing to listen with care to voices, music, sounds that are not easily audible and intelligible. The podcasts that were produced through the workshops were aimed at amplifying these sounds, enabling forms of listening that rely on the porousness of Melissa.3They may make more audible a politics of translation through which different femininities, races, social classes, ethnicities, religions, cultures, and languages become re-negotiated and interdependent. The sonic subjectivities that emerge in these porous spaces of translation, addressing many others, build bridges and resist both the perceptions of migrant women as a homogeneous group of strangers and the neoliberal logics of multiculturalism that treats their diversity as a source of profit and exoticism. The buzzing of translation is about imagining collectivity without unity, about subjectivities that come together not because they speak the same language or share the same experiences, but because they listen in common across gendered, cultural, linguistic, and racialized borders.