Sounding Border Natures: An Aural Contact with the Greek-Albanian Border

The hydrophone is immersed in the cold waters of the Gistova glacial lake at 2,353 metres altitude. A delicate sound comes through the headphones, as if the water is lighter, more crystal-like up here. It is a fairly windy day and small waves ripple the tiny lake’s surface. From time to time the gentle current carries the hydrophone onto a pebble, the impact producing a crackling sound that peaks and saturates the recording. I will need to ‘clean’ this later in the studio.

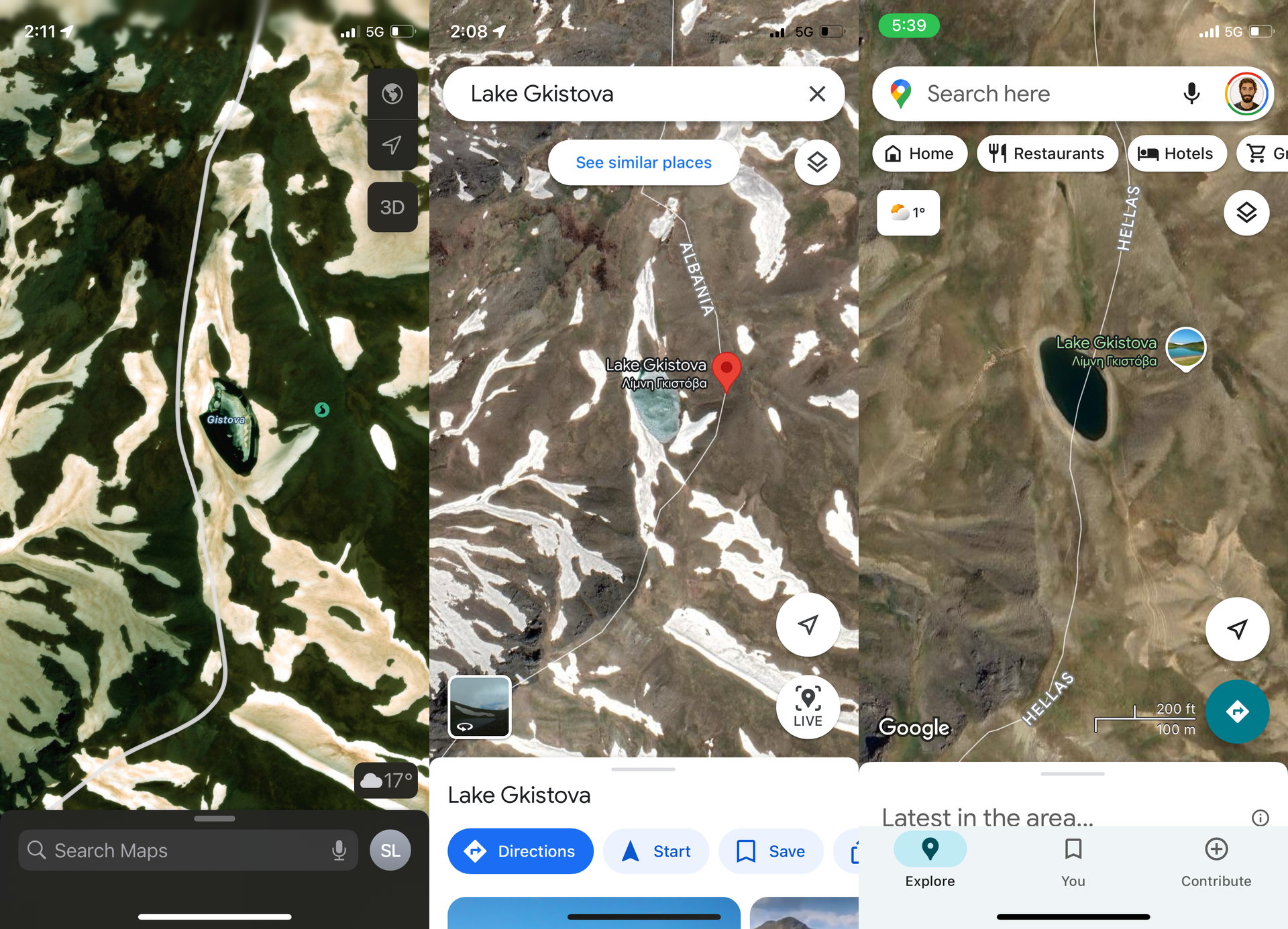

The ‘dragonlake’, as it is referred to by mountaineers, sits below the highest peak of mount Grammos, Tsouka Petsik, and along the border between Greece and Albania. State jurisdiction over the lake is unclear to me; different maps show different border lines. Apple maps assign the lake to Greece, and Google maps to Albania; other versions show it split between the two countries. When I hiked up there to record the lake waters with a group of friends, a thick fog draped the mountain, reducing visibility to a couple dozen metres. I could not see the concrete border demarcators along the ridge, known as ‘pyramids’, most of which would anyway be covered in a thick layer of late-spring snow, at places 3–4 metres high, now melting into the lake and downwards to the several torrents cascading the mountain slopes. I do not know where the recording was made vis-à-vis the border, and, though a lot of my work outside ERC MUTE deals with answering such questions,1 this time I decided to embrace this uncertainty as part of my aural practice. Either way, I was listening to the border. A border that is 100 years old.

First demarcated in 1925 by a tripartite committee of British, French and Italian military cartographers,2 the border follows the ‘watershed’ line: the line that follows the catchment basins defined by mountain streams, which does not always coincide with the ridgeline.3 The Grammos watershed births two rivers: the Aliakmon, which flows east into the Aegean, and the Sarantaporos, which flows north-west into Albania and discharges into the Adriatic Sea.

A thousand metres below the lake the microphone picks up the grey noise from the turbid streams of Aliakmon overflowing from the melting snow. This is the sound of water etching territory onto the terrain.

Viewed from here, so-called ‘natural borders’ scripted over mountain peaks and rivers appear to be in a state of continual becoming and transformation, constantly deforming, eroding, faulting, thrusting, subducting, moving laterally and vertically; folding. Some move faster, like the flow of the Sarantaporos river that carries sediment downstream to its confluence with the Aoos/Vjosa along the Albanian border; some move slower, like the tectonic plates of Adria, Eurasia and Africa that collide under the Albanian-Pindos cordillera, causing the Grammos range to rise (Tranos et al., 2010), slowly but surely. Excluding punctual geologic events, like volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and landslides, these movements leave little trace and are too slow for humans to perceive. Increasingly nervous due to ongoing climate change, these movements of the earth’s mantle put into question traditional cartographic logic, unsettling notions of place, localness, territory (Massey, 2006, pp. 33–48), and the very idea of ‘natural borders’ as impermanent and immobile, upon which so much of Western sovereign thought has been premised (Rousseau, 1756, quoted in Sahlins, 1990, pp. 1,423–1,451).4

In my research, I think of these dynamic and flexible boundary environments as border natures (Levidis, 2021). Crafted as a synthesis of nature, space, technology, and law, and connecting actors as diverse as border authorities, fences, technologies of surveillance, political and legal orders, human and non-human forms of life, border natures occupy a liminal position between states, mobilities, and species. They are the turning inside-out of natural borders: an inversal of the well-established socio-military trope, to critically include the multiple human agencies, and their insidious and extractivist use of ecological dynamics for the work of border defence. The change in order here is not incidental. Border comes before nature, precisely to render audible and emphasise the ways in which bordering processes actively reconfigure natural environments. Rather than describing territorial limits as simply scripted over natural backdrops, border natures refer to the agency of nature in border assemblages but also, inversely, to the agency of borders in shaping natural worlds, and in affecting both human and non- human forms of life, both directly and indirectly. When set next to each other, the two cross-pollinate to produce a potentially lethal hybrid.

Border natures go against anthropocentric approaches that understand nature as passive or inert matter but also sit uneasily with ecocentrist concepts that posit it as a separate realm that is entirely ‘external’ to human society. Instead, with this term I propose a theoretical device that operates transversally and intersectionally across the natural and cultural domains to place human worlds and constructs – like borders – within nature, but ‘as one of its constituent parts, rather than subject to its transcendental laws’ (Braun, 2006, p. 195). Border natures are complex, variegated socio-material assemblages. The nature nested within them is an intricate mesh where political, economic, technical, cultural, mythic, socio-atmospheric and organic dimensions ‘collapse into each other in a knot of extraordinary density’ (Haraway, 1994, p. 63).

Thinking with and through border landscapes in this way allows us to trouble naturalized understandings of borders and nationhood and to interrogate the emerging and past orders of state power that these enable and preserve. But how can a critical aural practice allow for a more capacitous understanding of ‘natural borders’ and the seemingly stable, and opposing, ontologies of borders and nature? How can it re-inform our understandings of agency, causality, and violence at the edges of nation-states? How can we sense, and challenge, these agentive forces and the violence these unleash on those who inhabit or attempt to cross it unauthorized. How can we render them audible?

When the mixed broadleaf and conifer forests extending over the slopes of Grammos mountain caught fire in the summer of 2007, the exploding ammunition – land mines, artillery shells, mortars, and aerial bombs – that remained scattered across the forest since the Greek Civil War (1945–49)5 prevented firemen from accessing the area from the ground (Kathimerini, 2007). During my hikes, I also came upon such unexploded shells peaking out of the bushes – one has to tread carefully in Grammos. The fire smouldered for days, the slopes exploding in its wake. The latent energy that was stored in the dormant ammunition activated the archival nature of the forest floor. The blasts served as indices of past violences, untreated and ever ready to thrust their way into physical and social space (Nixon, 2011, p. 225).6

This eruptive potentiality of the civil war-era bombs is strongly reminiscent of the way border communities were understood by the state throughout the 20th century. A 1928 quote from the Greek envoy to Paris, Nikolaos Politis, helps bring the argument home. Albanian-speaking minorities in Greece, Politis claimed, were ‘foreign bodies, continually filled with explosive materials’ (Hart, 1999, pp. 196–220).

As his position entailed, Politis was merely ventriloquizing the state line. During the negotiations of territorial limits between Greece and the newly-independent state of Albania, it was decided by the Great Powers that the border be determined on the basis of ethnographic rather than geographical criteria, and specifically the language ‘spoken in family life’ (ibid., pp. 196–220). As a result, a series of censuses were conducted in the fifteen-year period over which the border took shape, with public servants going door to door to eavesdrop. This rendering of domestic space into territorial demarcator meant the border now cut across kitchens and bedrooms. At the same time, it sentenced allophonous communities who found themselves assigned to the ‘wrong’ side of the border to silence and, for the most part, to uprootment, exile and erasure.7

*

I am writing this text a month after my visit to Gistova lake, during fieldwork along the Sarantaporos river. I am to walk its entire length, from its many springs on the ridges of mounts Grammos and Smolikas, to its confluence with the Aoos/Vjosa river on the border with Albania. After a week of hiking, my knees hurt, so I have taken a day off and sought shelter in a guesthouse just below the border ridge, in the village of Plikati.

Older residents in Plikati are bilingual – they speak both Greek and Albanian. This, they explain, is because in the winter months they would migrate with their large flocks of sheep to the nearby Albanian town of Ersekë, right behind the mountain, rather than to the plains of Thessaly or Thesprotia in Greece as most of the nomadic herders in the Pindus range did. Plikati belongs to a cluster of villages known as ‘mastorochoria’, or ‘masons’ villages’, producing renowned craftsmen – stone masons, carpenters, blacksmiths and painters. These craftsmen would form groups, known as ‘bouloukia’ and travel across Greece and the Balkans looking for commissions – bridges, churches, houses. This is a song recorded on a phone at the village cafe that speaks to this migratory craft.8

By the time I finish writing this paragraph, a day later, I have scaled the mountain and am now in the village of Aetomilitsa, also known as Denisko. Aetomilitsa was founded as a place of summer pasture by Vlachs, also nomadic herders, who speak their own language – Aromanian, heard (but not written) all over the Balkans. Border demarcation is hostile to these ethnic and linguistic complexities – ever so intense in the mountainous ‘shatter zones’9 of the Balkans – which it can never fully discipline (Scott, 2009).

During my stay in and around Grammos I have come across several old, rusty signs next to disused barriers. The yellow ones read ‘Surveilled Zone’, and the red ones read ‘Restricted Zone’.

These refer to the ‘Supervised Zone’ or ‘Zone under Surveillance’ that was established along Greece’s northern border by the Ioannis Metaxas régime in 1936. This 1,212-kilometre-long and between five and one hundred-kilometre-wide infrastructure of ‘barres’ ran the entire northern border of Greece, containing four hundred and twenty towns and villages in Macedonia, Thrace, a large part of Epirus, and northern Corfu. The ‘zone’ was designed to isolate the unwanted, culturally ‘other’ subjects living within it10 and to recast the ethnically diverse areas adjacent to the border into a buffer against the Balkan socialist states in the North and Turkey in the East (Rombou-Levidi, 2009, 2017). Until the 1980s the ‘iron curtain’ here folded over mountains, forests, and lakes, extending both outwards and inwards and assuming a thickness that hosted a dual regime of exclusion and subordinatory inclusion. In Grammos, these historical zonations, still present on the ground in the form of decaying signs and alive in collective memory, contribute to the creation of pristine landscapes that have been left relatively undisturbed for decades.

It is precisely in and through these overlapping spatialities that border natures are assembled, and that the intentional rendering of borderlands into ‘wild spaces’ – ones that are ‘naturally’ governed by violence – is achieved. Spaces that at first glance appear to be wild or natural and thus outside the space of civil law, but in reality are very much the result of a ‘flooding’ of this liminal space with violence through law and state presence or selective absence. A frontier, rather than simply a border.11

*

Hiking along the ridge up to the glacial lake12 I zig-zagged between the two countries continuously, as if the border was unimportant, or not there at all. As I did, I was reminded of a minor passage in the demarcation protocol13 which provided that in the outstanding case where the border is skirted by a pathway, then the inhabitants of both countries would be guaranteed free passage along this pathway. While this might be true of hikers, it does not apply equally to Albanian seasonal workers or asylum seekers who cross the ridge in illegalized and dangerous, potentially lethal, conditions.

But why come all the way up here to drop a hydrophone in the lake?

This is my way of eavesdropping back at the border, my kind of census. When most of the human inhabitants who witnessed the violence of border demarcation are either removed, replaced, or coerced into silence, one needs to be resourceful about how to access the archive. I choose to direct my microphone to the mountain environment, which has been so intensely hybridized and re-signified in the last century. In the process, I hope to record not just bird calls, but also muted border histories as these reverberate across and through the terrain. This move away from discursive forms of testimony gathering is not meant to further relegate coerced voices into silence – I acknowledge this danger – but to think of witnessing as a collective and more-than-human process. So that these pathways cutting the border can turn into wedges, and wedges can morph into faults.

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

This article has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101002720 – MUTE).

-

1.

This text draws on research conducted for the ERC consolidator grant MUTE – Soundscapes of Trauma: Music, Sound the Ethics of Witnessing (National Hellenic Research Foundation) since 2023, focusing on the multiple sonic registers of border violence. Border violence has also been central to research I conducted for over the past decade or so, as a member of the research agencies Forensic Architecture, Forensis and Forensic Architecture Initiative Athens.

-

2.

The demarcation of the border was first discussed at the London ‘Conference of the Ambassadors’ in August 1913. As with the border with Serbia, talks were postponed until after the Great War, when the tripartite committee was charged with its precise delimitation. The border was finalized in 1925 with a treaty signed between Great Britain, France and Italy in Florence (known as ‘the Florence Protocol’), and ratified by Greece in 1926.

-

3.

This legal-cartographic concept is common in the delimitation of mountain borders, for reasons to do with states’ rights to water usage. It demonstrates the pervasiveness of water in attempts to delimit the nation state.

-

4.

‘The lie of the mountains, seas, and rivers [in Europe], which serve as boundaries of the various nations which people it, seems to have fixed forever their number and size. We may fairly say that the political order of the Continent is in some sense the work of nature’ (Rousseau, 1756, quoted in Sahlins, 1990, pp. 1,423–1,451).

-

5.

During the war the ridges of Grammos were the theatre of major battles and were the last guerrilla-held territories to fall to the national army. Bombs craters and fragments still dot these slopes as wartime scars, as do the defensive positions built into the mountain by the partisans. To the trained eye wandering above the treeline, these scars are visible as changes in the landscape of the alpine meadows; out-of-place decomposing trunks, large piles of rocks, and craters stand out of the shrubs and grass that dominate the landscape at these altitudes. The few trees that persevere in the sub alpine and alpine zones rarely exceed 50cm in height, compressed for months by the weight of snow and beaten by the wind year-round. Their roots, strained by the lack of space, hold the thin layer of soil in place and their branches carpet the floor, yet failing to conceal the topography beneath. If the war modified the terrain, the harsh mountain environment preserved these traces of wartime violence, years after the conflict ended.

-

6.

As Rob Nixon writes on the latent violence of Iraqi minefields, ‘the[y] have assumed the sedimentary character of the nation’s layered conflicts’ (2011, p. 225).

-

7.

Beyond the more sinister exclusionary policies that the demarcation of the border entailed, the post- delimitation process of national incorporation was carried out through a subtler process of assimilation, which also revolved around language, and which often required the recruitment of the natural environment in efforts to erase allophony. Over the three-year period of 1926-1928 that followed the demarcation of the border, 2,479 non-Greek sounding placenames in the Greek territory were formally replaced by a committee composed of geographers, archaeologists, historians and linguists. So were the names of rivers and mountaintops.

-

8.

I am indebted to Petros Kollias for the impromptu recording, with my recorder running out of battery at the most wrong of times.

-

9.

James C. Scott speaks of ‘shatter zones’, geographically and materially diverse areas like ‘mountains, marshland, swamps and steppes, and deserts’, where ‘pattern[s] of state-making and state-unmaking produced, over time, a periphery that was composed as much of refugees as of peoples who had never been state subjects’ (2009, pp. 6–9).

-

10.

Albanian minorities (Chams) in Epirus and Corfu, in the West; Macedonian and Bulgarian minorities in the North; and Turkish and Pomak muslim minorities in Thrace in the North-East.

-

11.

Despite the two often being used interchangeably, the frontier is a radically different concept and spatial regime to that of the border. As the anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli points out, ‘the frontier is a concept, not a place. It is a way of imagining space so that various things can be done there. It attempts to govern action and things therein by describing the nature of the region as the limit to settled law, sociality, and meaning’ (2017). On the frontier, Povinelli notes, ‘ruthless tactics are justified; the law can be suspended in relation to them’ (ibid.).

-

12.

Thanks are due to Giannis Leontaridis, Maro Pantazidou, Angelos Takopoulos, and the Openmountain.gr crew for organizing this hike.

-

13.

Article 6 of the 1925 demarcation protocol.

Braun, B. (2006) ‘Towards a New Earth and a New Humanity: Nature, Ontology, Politics’, in Castree, N. and Gregory, D. (eds.) David Harvey: A Critical Reader. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 191–222.

Haraway, D. (1994) ‘A Game of Cat’s Cradle: Science Studies, Feminist Theory, Cultural Studies’, Configurations, 2(1), pp. 59–71.

Hart, L.K. (1999) ‘Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece’, American Ethnologist, 26(1), pp. 196–220.

Kathimerini (2007) ‘Οι νάρκες του Γράμμου’, Kathimerini, 4 August. Available at: https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/294197/oi-narkes-toy-grammoy/ (Accessed: 10 August 2007).

Levidis, S. (2021) Border Natures: The Environment as Weapon at the Edges of Greece. PhD diss., Goldsmiths, University of London.

Massey, D. (2006) ‘Landscape as Provocation: Reflections on Moving Mountains’, Journal of Material Culture, 11(1–2), pp. 33–48.

Nixon, R. (2011) Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Povinelli, E.A. (2017) ‘Three Imaginaries of the Frontier with Illustrations’, Frontiers Imaginaries. Available at: http://www.frontierimaginaries.org/organisation/essays/the-imaginaries-of-the-frontier-with-illustrations (Accessed: November 2017).

Rombou-Levidi, M. (2009) Dancing Beyond the ‘Barre’: Cultural Practices and the Processes of Identification in Eastern Macedonia, Greece. PhD diss., University of Sussex.

Rombou-Levidi, M. (2017) Lives Under Surveillance. Athens: Alexandria.

Rousseau, J.-J. (1756) Extrait du projet de paix perpétuelle de l'Abbé de Saint Pierre.

Sahlins, P. (1990) ‘Natural Frontiers Revisited: France’s Boundaries since the Seventeenth Century’, The American Historical Review, 95(5), pp. 1423–1451.

Scott, J.C. (2009) The Art of Not Being Governed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tranos, M.D. et al. (2010) ‘Faulting Deformation of the Mesohellenic Trough in the Kastoria-Nestorion Region’, Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 43(1), pp. 495–505. Available at: https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.11200

Recording the Gistova ‘dragonlake’ on the Greek-Albanian border, May 2024

Photo credit: Magdalini Pitsou

This article develops an aural methodology for interrogating the historical and ongoing production of borders through the case of the Grammos mountain range along the Greek-Albanian frontier. Drawing on field recordings made in and around the Gistova glacial lake and the Sarantaporos watershed, it examines how hydrophones, environmental sound, and embodied listening can reveal the dynamic, more-than-human forces that unsettle conventional understandings of ‘natural borders’. The analysis situates contemporary sonic encounters within a century of territorial demarcation, militarisation, ecological transformation, and linguistic and ethnic regulation – from interwar boundary-making and civil war munitions to Metaxas-era surveillance regimes and present-day migratory constraints. To conceptualise these entanglements, the article proposes border natures: socio-material assemblages in which natural processes, state power, ecological change, and human and non-human agencies co-produce frontier environments. By listening to glacial lakes, melting snow, sediment-laden rivers, explosive residues, and local oral traditions, the study argues that sound offers access to forms of archival presence that exceed human testimony and disturb state-imposed silences. Ultimately, it shows how critical aural practice can sense, render audible, and contest the agentive geologic, political, and atmospheric forces through which borders are continually reconfigured – and through which they enact violence on those compelled to traverse them.

Keywords: border natures, critical sonic research, audible frontiers, Greece, Albania

Stefanos Levidis is an architect, spatial researcher and adjunct professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts. He is the co-founder and co-director of Forensic Architecture Initiative Athens (FAIA). Currently a research fellow, Levidis has worked with Forensic Architecture and Forensis since 2016 as a senior researcher overseeing the agencies’ work on borders and migration. He holds a PhD from the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, titled ‘Border Natures’, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the National Hellenic Research Foundation under the project MUTE. His spatial and visual practice has been presented and published internationally, and his investigative research has been submitted to courts in support of human rights cases.

Levidis, S. (2025) ‘Sounding Border Natures: An Aural Contact with the Greek-Albanian Border’, Witnessing, 1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.26238/witnessing.2025.01.08